A period room

station

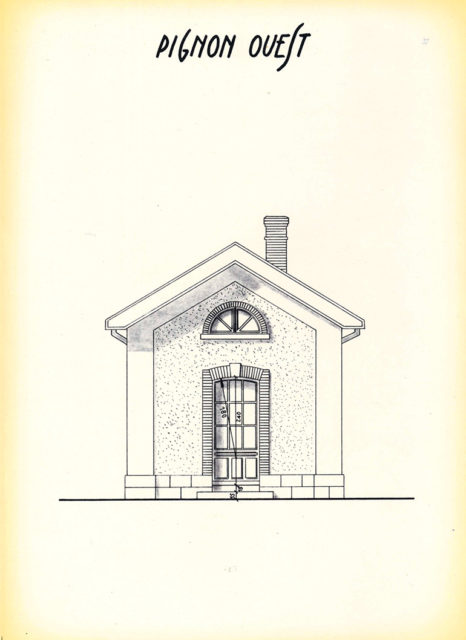

From the earliest days of the museum, Michel Doerr defended the idea that railways are a complex system that needed to be treated as a whole. Between buildings A (rolling stock), B (reception, offices and restaurant) and C (firefighters’ museum), the outside area welcomed a collection dedicated to infrastructure. So it was that in 1982, the idea of a small station was proposed. It was created out of nothing, to reconstruct the office of a station master and show visitors the atmosphere of a small station. In the museum, engines made by the SACM, decorative arts, fine arts and models, such as the Vitry test bench, now completed the display.

The electric cube

1983 was a good year for the French Railways Museum. Over those 12 months, the organisation experienced a historic peak of visitors, totalling 239,807 people. At the same time, the museum was given the Prestige de France award. It was the first museum in the provinces to achieve that distinction, to the joy of its founders Jean-Mathis Horrenberger and Michel Doerr, who was about to resign from his position as Director.

“[…] you promoted the idea, brought together all the goodwill, drove the convergence of efforts, then after becoming the Director of the museum in gestation, you defined the floor plan and specified the details. One wonders from where you derive the power to turn a childhood dream into a reality admired by over a million visitors.”

– Award to Michel Doerr of the decoration of the Légion d’honneur, speech by André Portefaix at the ceremony of 19 October 1983

In the autumn of my life and in line with philosophy, I ask him [Jean Renaud, future director, editor’s note] to meditate this first Hippocratic aphorism:

– ars longa, vita brevis – which could be perfectly transposed from medical science to the archaeology of the railways; for it was you, my dear Engineer General, who helped us save those who needed saving, if only the famous salon for Aides-de-Camp. Thank you!

– Reply from Michel Doerr to André Portefaix

From the office windows, the decorated team carefully watched the comings and goings of cranes and trucks. A new building was emerging on Rue du Pâturage. This was the centre of energy, which would become Electropolis. Five years after the saving of the Sulzer-BBC machine of the company DMC, the outer walls of the cube were being erected. The EDF museum, designed by the architects Morin and Fanuele, opened in 1987 and inaugurated in 1992, set out to display the epic of electricity. The institution is developing all the time, and offers a space dedicated to innovation since 2018. A rotor from the nuclear power station of Fessenheim, which arrived in the night from 6 to 7 April 2021, stands proudly at the centre of the electric garden. This 153-tonne object is the latest large acquisition of the partner museum.

A museum with

appetite

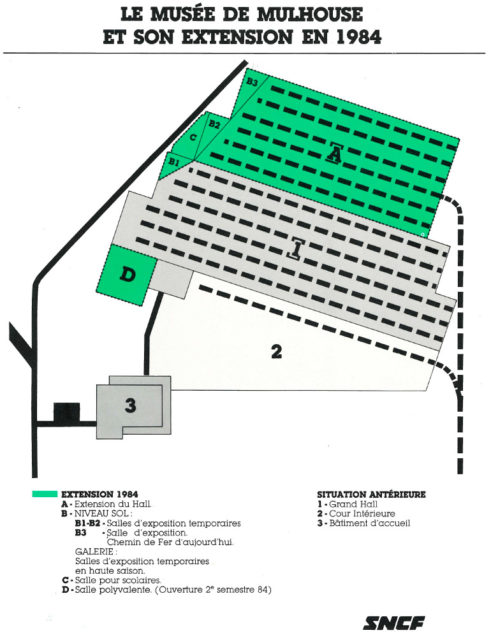

From 1976 to 1984, the collection grew continuously and visitors got an opportunity to attend the arrival of the steam locomotive 032 Engerth no 312 L’Adour (in 1978), the locomotive Ten Wheel (in 1978) and the electric car Sprague BDF 9011 (in 1979). In a note of 1979, Michel Doerr remarked that Mulhouse has a “large appetite”. That could only mean one thing: the building needed to be extended. That decision had in fact been approved in 1978 by the board of directors on 19 December. Once again, the architect Pierre-Yves Schoen was commissioned to help the museum in its projects.

On 15 May 1984, a special train was chartered for the public opening ceremony of the second part of the works. Inside the museum, now covering almost twice its initial area, known figures could be seen. They included René Clément, maker of the famous film La Bataille du Rail, Bernard Lemoine, President of the Prestige de France committee, and André Chadeau, Chairman of SNCF. The last of these was certain that the TGV would soon have a place in the establishment. And he was right: the TGV did come to the museum.

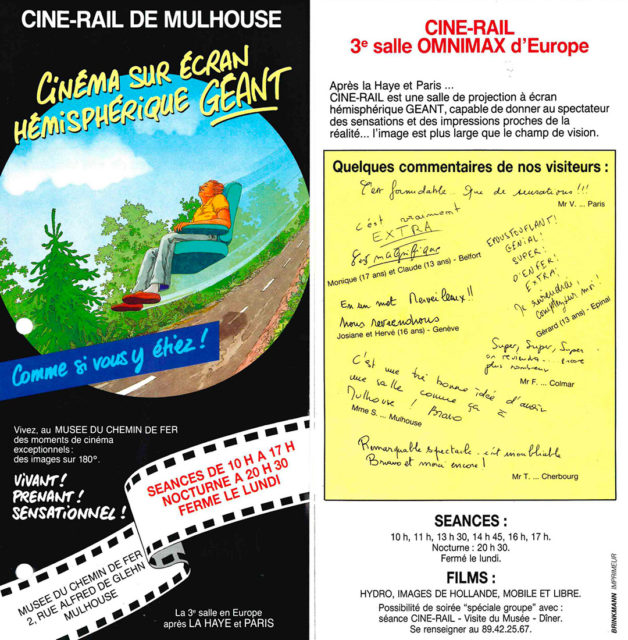

Ciné-rail

While the hall dedicated to rolling stock was significantly extended, gifts of archives, works of art and small objects kept flowing in. At the same time, visitors were to be offered an ever renewed experience. That was how the creation of a cultural dome was proposed. The structure built in 1987 was connected to the offices by a covered corridor, and was comparable to the Geode, inaugurated in the Cité des Sciences in Paris in 1985. This ring-shaped building was a true architectural feat, characterised by its cupola made up of 32 pieces prefabricated by the contractor Savonitto.

Under its domed roof, a screening room was installed, marking the birth of the Ciné-rail. This panoramic cinema was the third Omnimax theatre in France, with 99 seats, and was intended mainly for screening documentaries. Hydro and Images de Hollande were among the catalogue of short films shown between 1989 and 1990, offering visitors and cinema buffs of Mulhouse “sensations and images that will take your breath away!”

A locomotive

named Museum

In 1989, while Alsace was celebrating the 150th anniversary of the Mulhouse-Thann line, the French Railways Museum passed another symbolic milestone. One year before the departure of Jean-Mathis Horrenberger in 1990, the BB 26006, also known as the “Sybic”, was decorated with a blazon showing the museum. Blazons, which are visible on the liveries of rolling stock when it is inaugurated, generally use the symbols of their sponsor cities. That of the museum thus joined a huge collection, particularly with the arms of Reims, Valenciennes, or Aix-les-Bains.

“Voyage in the world

of railways”

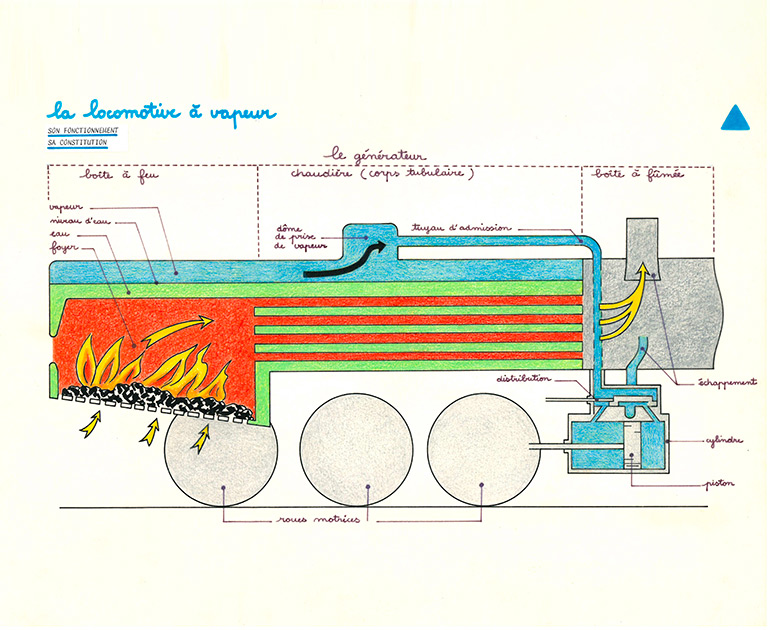

From the 1980s, the Railways Museum increased its cultural mediation efforts. Educational elements that were distributed “at large” emerged, such as teaching kits. Three such kits were developed voluntarily in 1983 by a group of teachers and offered to classes in the Mulhouse area. They addressed technical subjects such as the working of steam, and also links between railways and art, literature, geography etc.

Ten years on, in December 1993, a new teaching space was inaugurated in the former Ciné-Rail building: the Express Museum: voyage in the world of railways. This 220 m² space was opened to the public on 15 January 1994, and covered 31 different subjects related to railways. It enabled children, and non-specialist adults, to explore the collections of the museum and gain a better understanding of them. Until it was closed at the end of the 1990s, its passage way included a variety of complementary objects such as animated models, display objects, games, photographs and engravings.

“A coffee, one last ride, and we leave!”

In 1995, a new museum poster claimed that the museum was unforgettable. The great witnesses queried as part of this retrospective agree. With new objects, visitors, personalities and events, each one of them has a vivid memory of their relationship with the institution.

The restaurant was a key element in that experience, with the formal and information exchange fostered by the delicious fare of Alsace.

Located on the first floor of the office building, the restaurant was also the “canteen” for office employees of La Mer Rouge district. And while their parents enjoyed a cup of coffee, children clambered onto the little train which went around the cultural dome.

15 km per hour is a lot when you are little! Especially when the train is in reverse!

“Discover a great museum and its magnificent collection. Come admire our marvels in Alsace, so full of surprises. Mulhouse is not so far away from you.”

– Slogan of an advertising poster published in 1995

Mulhouse, capital of technical museums

On 4 December 1993, l’Alsace bore the title “Museums without borders are here!” This initiative of Mulhouse, forerunner of the present-day MMSA (Musées Mulhouse Sud Alsace), consisted in forming an organisation aimed at “boosting the museum potential of Mulhouse”. The Fine Arts Museum (1864), the History Museum (1868) the Fabric Printing Museum (1955), the Railways Museum (1971), the National Automobile Museum – Schlumpf collection (1982), the Wallpaper Museum (1983) and Electropolis (1992) together form a rare multidisciplinary collection. Common programming and communication have enabled them to turn Mulhouse into a capital of technical museums.