BIRTH OF

THE RAILWAYS HERITAGE

The 19th century was the century of the railways. Along the tracks, in the aisles of Universal Exhibitions, in art and in media, the public gradually discovered the wealth of the new railway heritage.

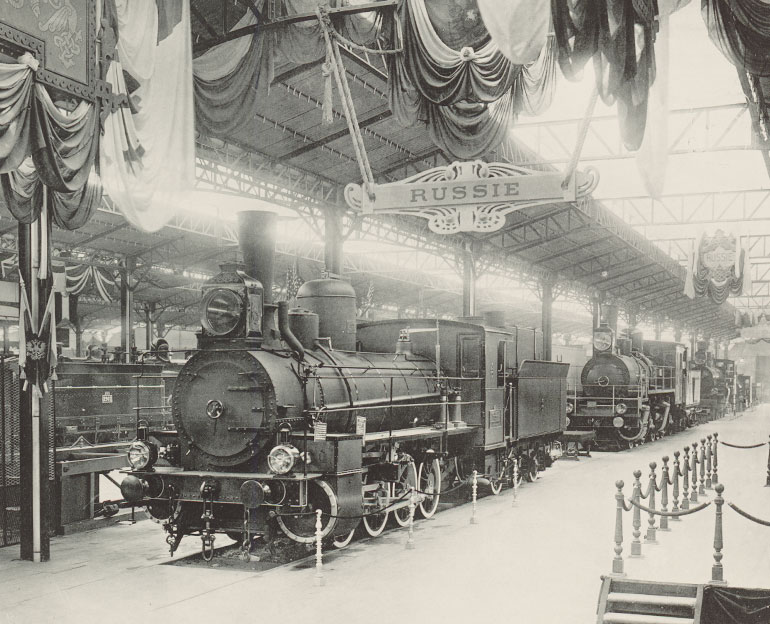

Paris. 1900. A strange invention appeared: the moving pavement, also called the “rue de l’Avenir”. The mechanism drew great crowds, but was no match for its underground counterpart, the Metro. The first Metro line was inaugurated at the Universal Exposition of 1900, and ran between Porte Maillot and Porte de Vincennes. The crowd was thick at the station exit. The great railway equipment pavilion, built near Daumesnil Lake, exhibited engines and carriages from across the world.

At the dawn of the 20th century, the usefulness of the railways was no longer debatable. They were a part of daily life, and had already made many an appearance in the arts. At the end of the Exposition of 1900, Maurice Bixio, Director of the Compagnie Générale des Voitures in Paris came to the conclusion that France needed a “permanent museum” of means of transport. That statement, often believed by historians to be the starting point of the adventure of the French Railways Museum in Mulhouse, may also be considered to be a sign of the awareness of heritage from the very outset of the steam age.

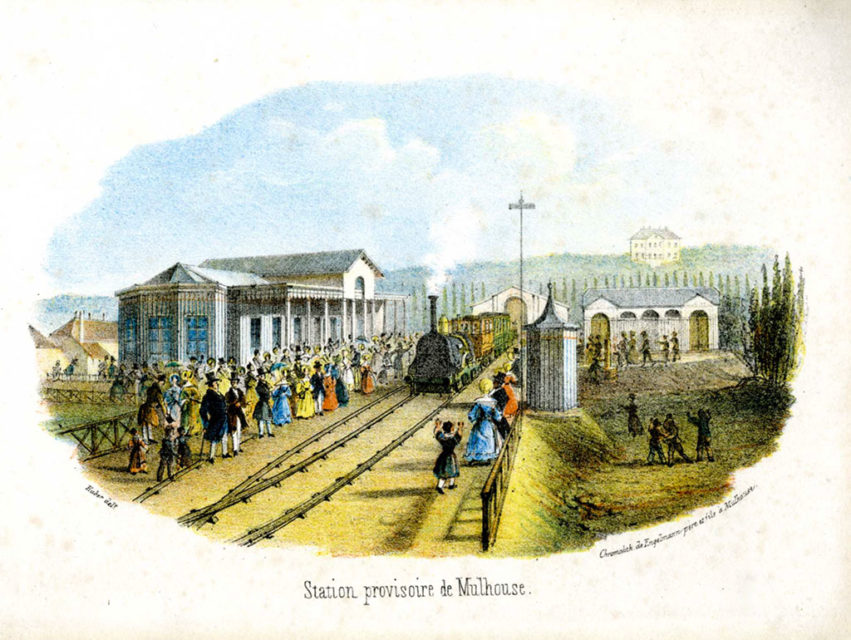

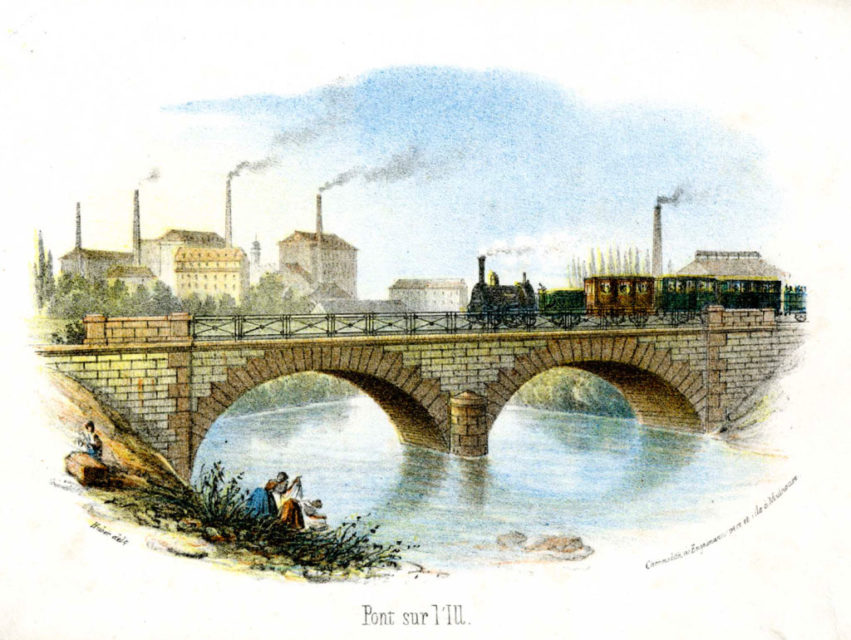

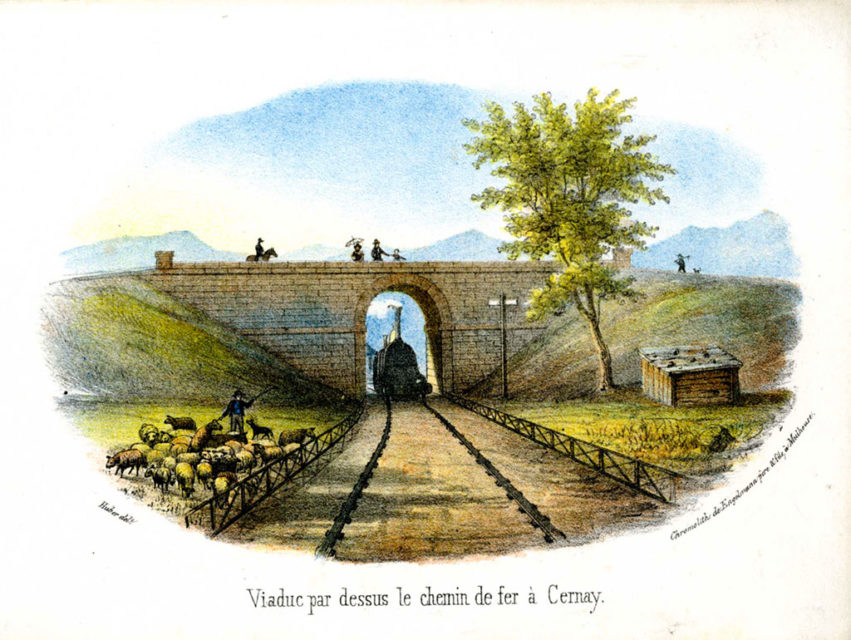

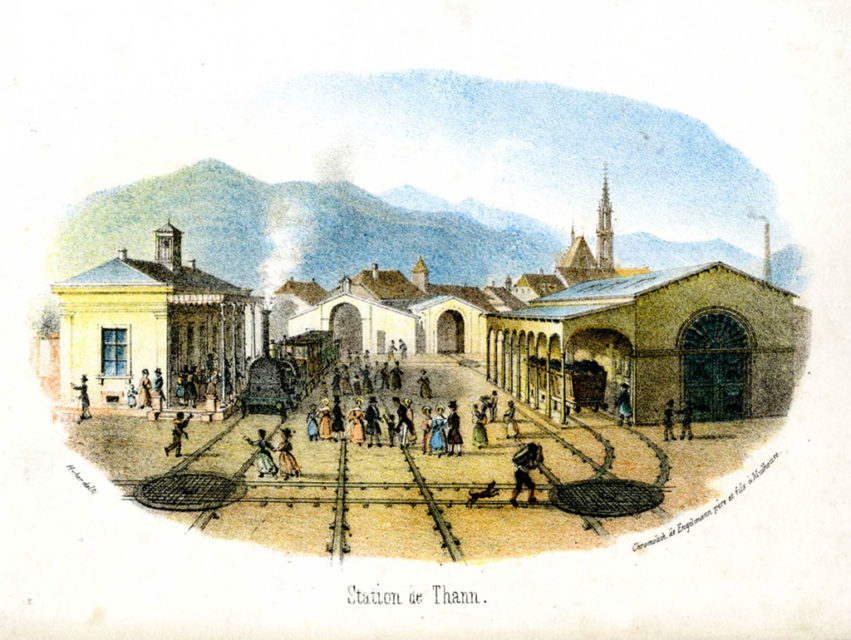

The railway line between Mulhouse and Thann was inaugurated on 1 September 1839. 130 years later, in 1969, Mulhouse was selected as the future home of the French Railways Museum.

A railway

show

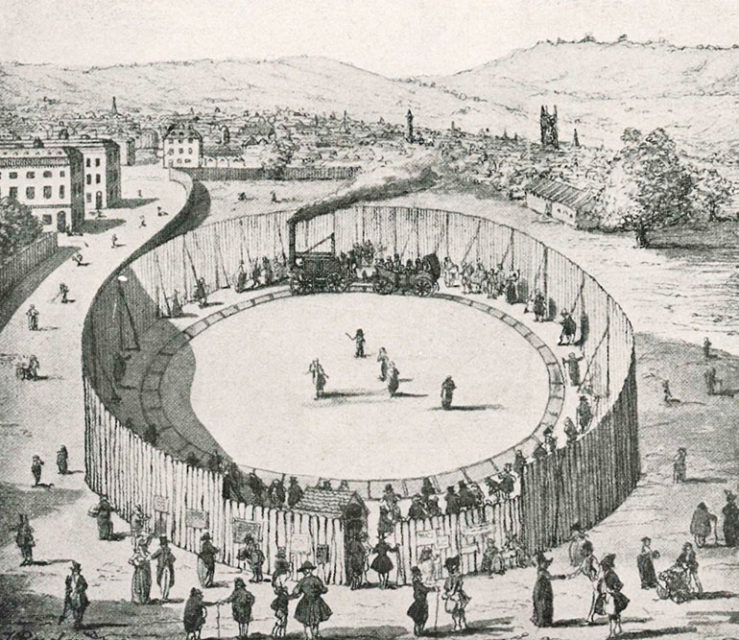

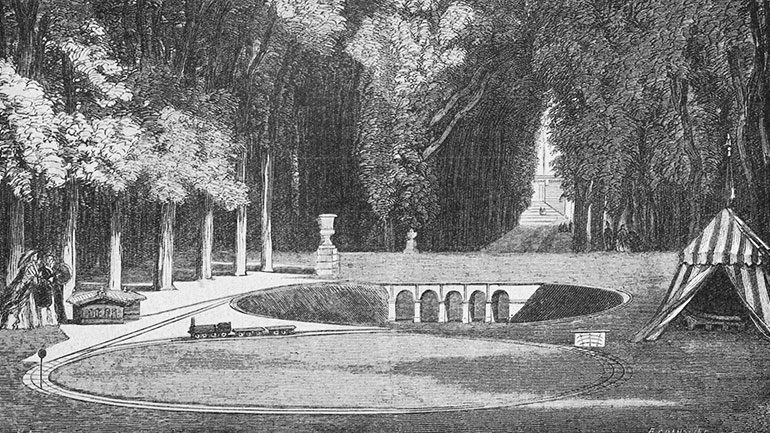

Where does the history of railways start? While one may be tempted to go back in time to the first sledges used in ancient Egypt, to the first rutted Roman roads or the wooden tracks of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the 19th century will remain the golden age of railways. Catch Me Who Can may be identified as the first demonstration steam locomotive. This four-wheeled machine created by Richard Trevithick in Britain was presented to public in London in 1808. That steam machine ran on a 200-metre long circular track and reached a speed of 20 km per hour. The large crowd were admitted to the novel “steam circus” for a price of five shillings. While the most daring enjoyed a turn on the single carriage, the inventor, on the brink of ruin, was sure of one thing: the ride was a harbinger of what would eventually become one of the greatest inventions of contemporary times: that of rail transport.

“A small sketch

of history”

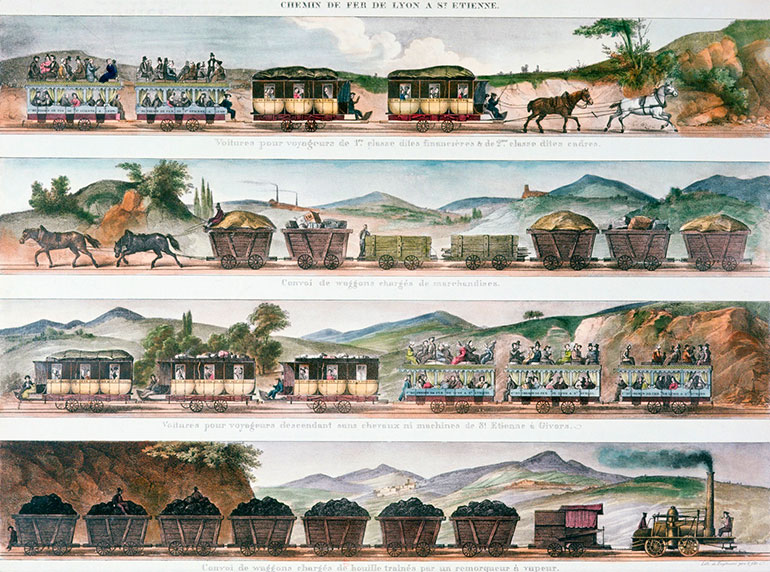

Founded in 1833, Le Musée des Familles, Lecture du Soir aimed to provide a “complete lesson of familiar, amusing and varied education for all”. This richly illustrated periodical was intended for a wide readership and one of its first articles was devoted to railways. After starting out with the indication that railways are still “not well known in France”, the writer describes the development of goods transport by rail using two examples: the British line between Manchester and Liverpool (1830) and that in France between Saint-Etienne and Andrézieux (1827). Picturesque engravings supplemented by technical diagrams gave subscribers an opportunity to discover what was said to be a developing mode of transport. Indeed, while England had already inaugurated its first passenger line between Stockton and Darlington (1825), work was under way in France, particularly led by the Séguin brothers.

The mystery

of movement

“It is sad to think that out of the thousands who travel every day from Paris to Saint-Germain, no more than twenty have taken the time to study the mystery of the movement that is carrying them, and are capable of speaking of it with any clarity. […] Could the authorities not do something to stimulate and encourage public curiosity in this area? Every time an important new machine is accepted by science and industry, would it not be of use to give the public an explanation, every Sunday, in a special venue, such as the Conservatoire des arts et métiers?”

Le Magasin Pittoresque, 1837

1835. For the first time, the Academy of Sciences published weekly minutes of its meetings. That publication, which was driven by François Arago, provided its readers with a precise review of current science news and debates. Eight years after the start of the line between Saint-Etienne and Andrézieux in 1827, these documents reveal the discussions within the scientific community. While treatises devoted to steam grew in number, they were however reserved for a select few.

Thus, in 1837, after the inauguration of the first French passenger line between Paris and Saint-Germain-en-Laye, a journalist writing for the Magasin Pittoresque lamented the continuing ignorance of the public when it came to the working of steam engines. To remedy that, he defended the use of “public explanation” sessions at the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers.

A place in the

conservatory

The Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers was founded in 1794 by Abbé Grégoire, and is a repository for a rich collection devoted to the railways. In his book published in 2007 named L’amphithéâtre, la galerie et le rail, Lionel Dufaux reminded readers that the first railway-related acquisition dates from 1824. A study of the inventories, catalogues and stock-taking documents dating from the 19th century also shows that the railway collection developed significantly under the July Monarchy. In 1843, writers for the Magasin Pittoresque thus described their tour of the establishment: within the great gallery, models of rails and cutaway views of locomotives at 1:5 scale showed how steam engines work. Ten years later, on 28 January 1853, in correspondence that was brought to light by Lionel Dufaux, Théodore Olivier, former director of the museum, stressed the main issues relating to the exhibition of life-sized rolling stock. He said: “[…] in a few years, the whole of Paris would not suffice to house all these new models that some of my colleagues dream of.”

A railway in

Alsace

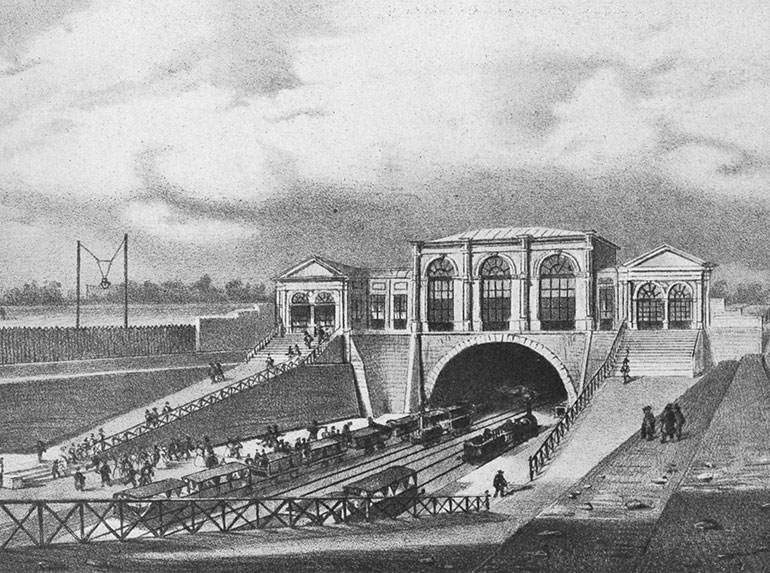

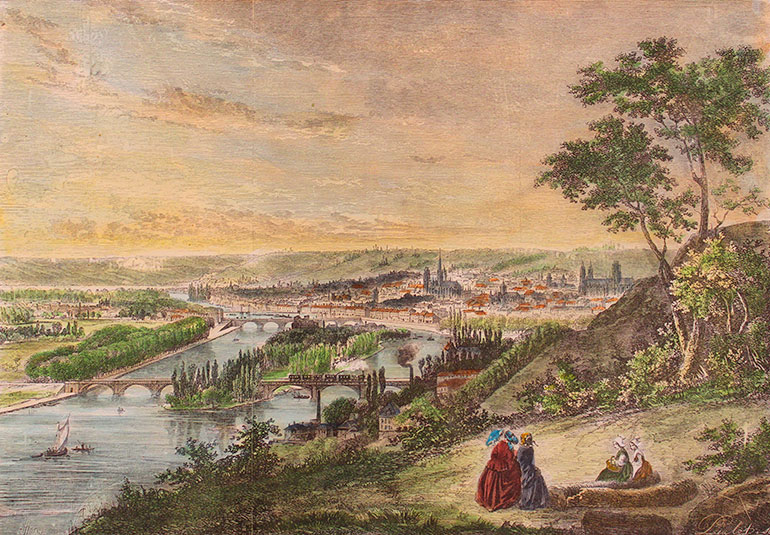

While the institution in Paris continued to add to its railway collection, the railway came to Alsace. In 1839, the inauguration of the Mulhouse-Thann line marked an important stage in the development of passenger transport. The event, which drew a large crowd, was the culmination of an ambitious project promoted by Nicolas Koechlin. Top hats, crinolines and parasols came out in a setting that brought together the Vosges mountains and engine smoke. The train was led by the Napoleon locomotive made by André Koechlin et Compagnie (forerunner of the Société Alsacienne de Constructions Mécaniques), which soon became a symbol of the know-how of Mulhouse. In 1841, Strasbourg-Basel became the first international rail link. Over a century later, these historic episodes would contribute to the birth of the French Railways Museum in Mulhouse.

– Act of 11 June 1842, after 1842, Dollfus collection stored at the Cité du Train

French Act of 11 June 1842

“Article 1

Act relating to the establishment of trunk railway routes

A railway system shall be established, directed, 1 From Paris

To the border with Belgium, through Lille and Valenciennes;

To England, through one or more points on the channel coast, to be determined at a later time;

To the border with Germany, through Nancy and Strasbourg;

To the Mediterranean sea, through Lyon, Marseille and Cette;

To the border with Spain, through Tours, Poitiers, Angoulême, Bordeaux and Bayonne;

To the Ocean, through Tours and Nantes;

To the centre of France, through Bourges;

2 From the Mediterranean sea to the Rhine, through Lyon, Dijon and Mulhouse;

From the Ocean to the Mediterranean, through Bordeaux, Toulouse and Marseille.”

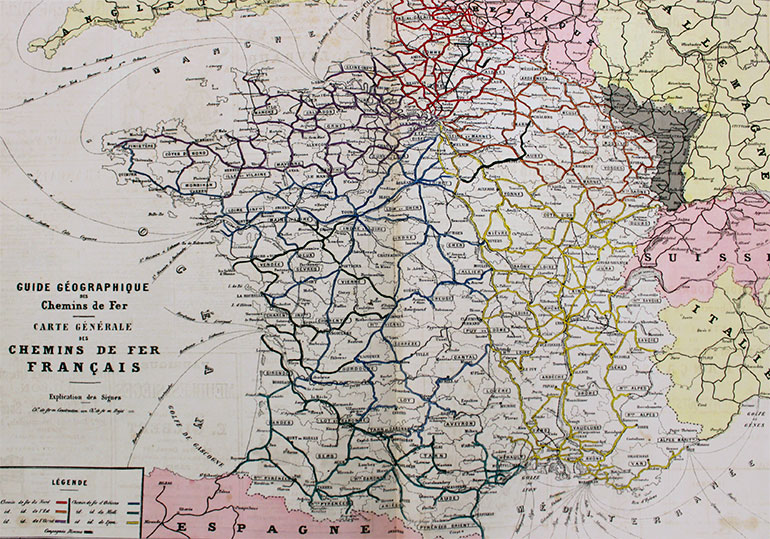

Promulgated by King Louis-Philippe, the Act of 11 June 1842 redefined the map of France. In its nineteen articles, the law established the future railway network from a central point: Paris. Along with the confirmation of that configuration, which was called the ‘Legrand star’, the government set out a number of financial and policy arrangements. For example, if a company agreed to pay for the construction of a line, the government agreed to give it a monopoly on the operating area. While the law led to increased speculation and the coming of players such as Rothschild’s Bank, it also helped the growth of the main railway companies, which continued to operate till the SNCF was founded in 1938.

Early

companies

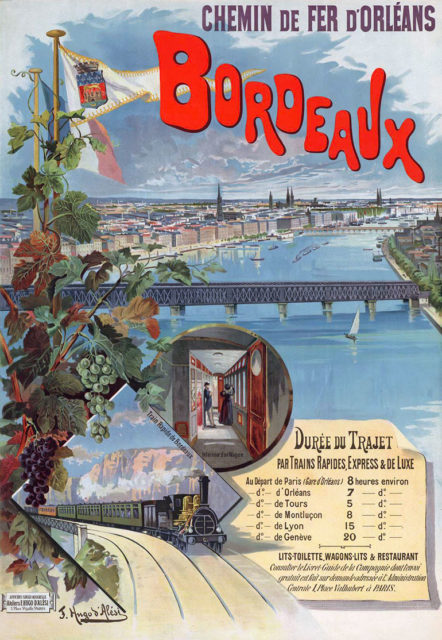

As the months passed, the railways spread their web along the roads, through forests and across rivers. Across France, railway lines mushroomed, carrying goods and passengers. As part of that unprecedented geographical, technological and social revolution, businesses emerged, grew, disappeared or joined forces. A review of the Journal des chemins de fer et des progrès industriels, published in 1842 for the first time, gives an insight into this far-reaching phenomenon. By the end of the Second Empire, six main railway companies dominated the market. These were Compagnie du P.O. (Paris-Orléans, 1844), Compagnie du Nord (1845), Compagnie de l’Est (1845), Compagnie du Midi (1852), Compagnie de l’Ouest (1855), and Compagnie du P.L.M (Paris à Lyon et à la Méditerranée, 1857). They were very often modelled by a colour code covering every centimetre of the map of France, and were the bearers of an extraordinary tangible and intangible heritage.

The emergence of a

railway-worker identity

A railway network is not limited to routes, trains and passengers. It is a tentacular system that includes station architecture, workshops, depots, switches, and developments in signalling and rolling stock. People cannot be separated from engineering, and they are symbolised by the great diversity of trades involved and the profiles of passengers. Against that backdrop, each company developed an organisation, values and an aesthetic that were specific to it. The uniforms of railway employees were a particular sign of that sense of belonging.

Between wariness and fascination

Saying that the coming of the railways was unanimously applauded by the thinkers of the 19th century would be inaccurate. Enchantment and optimism were also accompanied by fear, incredulity, sarcasm and even staunch refusal. The vaudeville show of Salvat and Henri named Le Chemin de fer de Saint-Germain that was put on in the Théâtre de la Porte Sainte-Antoine represents the caustic approach to this new invention, described in the play as a another “fad”. In his Mémoires d’un touriste, Stendhal, residing at Châlon-sur-Saône on 14 May 1838, also regretted the excessive importance given to the productions of “modern civilisation” such as “Diorama and railways”.

It is ironic that a century later, the same city of Chalon would host the first trains that were conserved as heritage objects with a view to creating a French Railways Museum. From the very beginning of the railways adventure, the historical and political character of this mode of transport came to the fore in the press and literature. Defending railways amounted to defending a regime. That was so of the writer and critic Jules Janin, who was close to King Louis-Philippe, and went so far as to say in his Itinéraire du chemin de fer de Paris à Dieppe (1847) that “poetry in the 19th century is that of the steam engine”.

“… If you find the subject (of railways) boring, you are just like me. Nowhere can one escape people saying: “Oh! I am off to Rouen! I have come from Rouen! Are you going to Rouen? The capital of Neustria had never been such a subject of conversation in Lutetia! …”

– 9 June 1843, letter from Gustave Flaubert to his sister Caroline Flaubert

The railway

as a character

In literature, railways are both carriers and characters. The century was marked by the birth of the concept of historical monuments, and that of picturesque stories. By reducing time and distance, the railways contributed significantly to their development. Stendhal, George Sand, Gustave Flaubert and Victor Hugo travelled by rail and told of their experience. In a famous letter sent on 22 August 1837 to Juliette Drouet, the author of Notre-Dame-de-Paris had this to say about his discovery of the Belgian railways. Comparing the engine to a “true beast” Hugo gave it the characteristics of a horse: “it sweats, trembles, whistles, neighs, slows down, rushes away”. A study of contemporary writings shows that personification is very common. A train is a creature full of sound and smell, which excites the senses. In that area, one cannot avoid mentioning La Bête humaine by Zola and Around the world in 80 days by Jules Verne. At the same time, words were joined by pictures. Monet, Courbet, Caillebotte, Van Gogh, Louis Lumière and so many others portrayed the railways in paintings and on film, making them a very artistic subject.

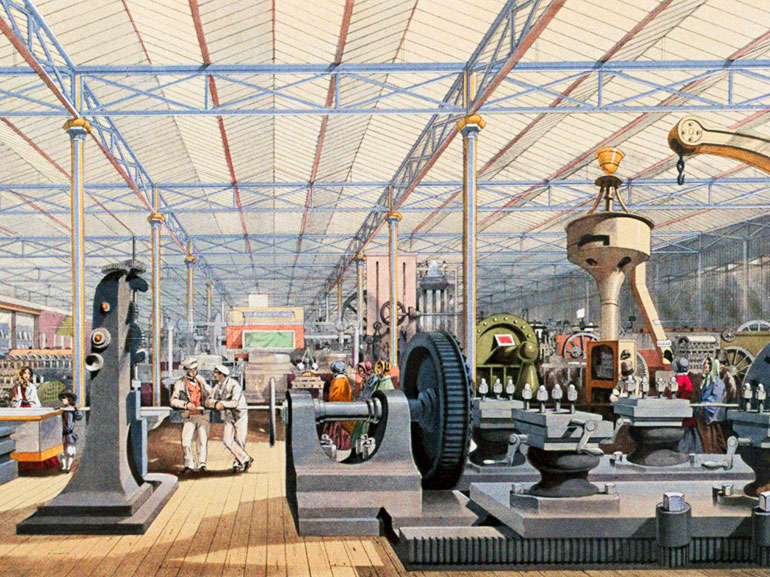

Exhibiting industry

While the public can discover the railways through the tales told by their contemporaries or their own experience of mobility, exhibitions of the products of French industry also showcased the development of railways. These major events were organised in Paris as early as in 1798, to highlight French know-how in a wide variety of areas including textile, cabinet making and metallurgy. A review of the judges’ reports provides valuable information about the representation of the railway industry.

In 1823 and 1827, steam engines were mainly used in farm machinery. In 1839, a great change occurred, when the Railways section first appeared. In the mind of the writer, in spite of the inauguration of the first railway lines, there was no doubt that rail transport was still in its infancy. The author also stressed that France was lagging behind her neighbour across the channel. In 1844, the section was supplemented by a new category, that of “Locomotive machines and railways, tracks and cars”.

One of the gold medallists was Meyer et Cie from Mulhouse, developers of a locomotive named L’Espérance, which was delivered for the Strasbourg Basel line in 1842, soon followed by the Mulhouse, which had been set aside in 1843 for the Paris to Versailles line. The silver medal went to the workshop in Rouen of the Englishmen Allcard and Buddicom, who had created the oldest European locomotive that can be still be found in the Cité du Train, the 1844 Buddicom.

Five years later, in 1849, the judges’ report became even more precise, and now spoke of “Construction of locomotive machines, brake vans, parts and miscellaneous equipment”.

While Derosne et Cail displayed a Crampton system locomotive, other companies presented track components, workshop drawings, car buffers or machines that printed numbered tickets. The public could thus discover the diversity of railway heritage.

The Crystal

Palace

In 1851, the phenomenon of industry exhibitions went global. Under the glazed roof of the Crystal Palace in London designed by Joseph Paxton, the British advance in engineering and commerce was put on display. The building was originally erected in Hyde Park and was a temple to the Industrial Revolution, hosting a large number of countries that brought their latest artistic and manufacturing creations with them. For one of the main British reporters, John Tallis, the display from France was second only to the United Kingdom in terms of its quality. According to the author of the report, exhibitions of industry products organised in the past in Paris were bearing fruit: the objects presented by the 1750 exhibitors showed a keen sense for detail, not unlike what we would now call “scenography”. Thus, the plan of the palace tells us that on the ground floor, near the aisle devoted to locomotives, a large stall showcased “moving machines”. Indeed, the understanding and promotion of printing and spinning machines required the use of animation.

Behind the scenes in 1855

“Machines cannot be put into motion without being directly supplied by fuel; machines create inconvenience because of their noise and smoke, or because they take up space. That it why steam locomotive engines, nailing machines, distilling equipment, beaters and so on may only be displayed in the galleries in their idle state”.

– Report on the Universal Exposition of 1855, Napoléon-Joseph-Charles-Paul Bonaparte

The London event had left a lasting effect on visitors. As a result, Paris had to do its best. Four years after the Crystal Palace success, France inaugurated its first universal exposition. The report drafted by Napoléon-Joseph-Charles-Paul Bonaparte, the Emperor’s cousin, was of importance against that background, as a remarkable testimonial of the Titanesque preparatory work required by such an event. Indeed, bringing together so many exhibitors is not easy, especially when their intention is to display large objects like railway rolling stock. The writer stressed that the organisation of the Gallery of Machines therefore led to a certain number of compromises. In particular, he pointed out that locomotives, which generated noise and smoke, could only be shown halted.

Trains as

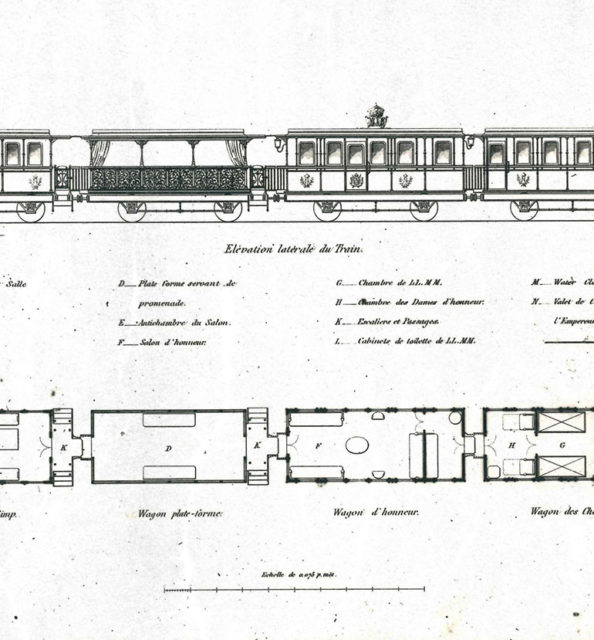

ceremonial spaces

Two years later, while London was inaugurating its Science Museum, the imperial train showed a significantly more delicate aspect of railways. Built by the Compagnie du chemin de fer d’Orléans for Napoleon III and his wife Eugénie, the train was made up of six carriages. These spaces, built under the supervision of the engineer Camille Polonceau based on drawings by Eugène Viollet-Le-Duc, were truly palatial and included a dining room, pantry, salon for aides-de-camps, antechamber, ceremonial room, bedroom, lavatory and wardrobe. A book published in 1857 by the publisher Bance tells us that the composition required five months of work. Salon 6 for Aides-de-Camps can be seen in the Cité du Train, a remnant of that artistic prowess. The car was restored in the 1970s by the Romilly workshop and is decorated in garnet and ultramarine blue. The imperial eagle and the bronze columns give it its refined appearance. Inside, the Emperor’s monogram is encased in a sophisticated floral decor. The types of wood and expensive fabric used create an atmosphere that is warm, yet formal. Salon 6 is a symbol of the eclectic tastes that were in fashion at the time, and is a masterpiece in movement.

1867 and 1878:

Station and mechanics

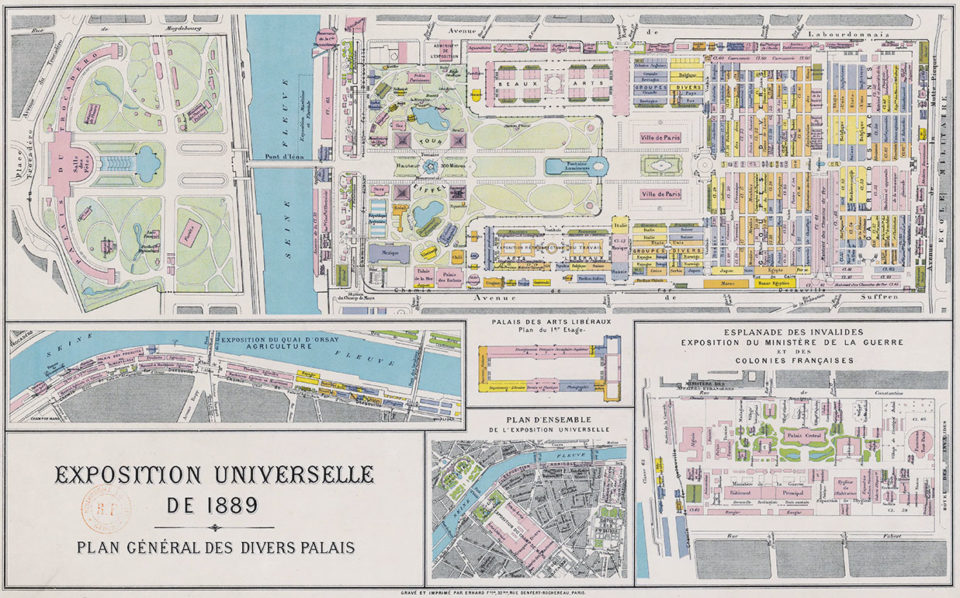

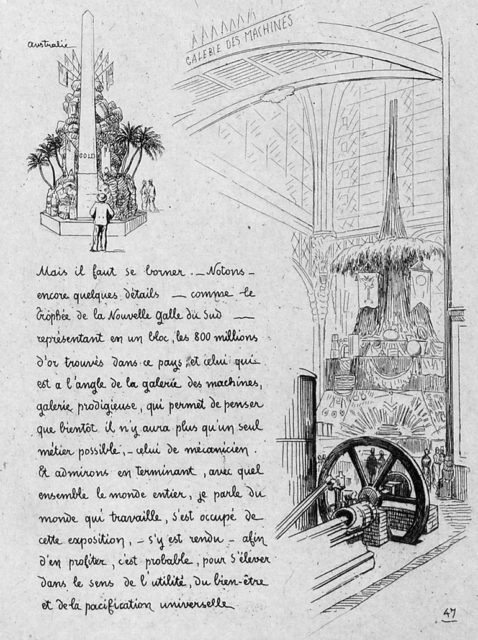

But there is much more to trains than ceremony and demonstration. At universal expositions, they also bring in a large number of exhibitors, objects and visitors. As a result, the organisers negotiated with the companies to make the event a success. At the Exposition of 1867, the “belt railway” was thus linked to one of the entrances to the exhibition. 31 inbound and 28 outbound trains carried the public to and from the event. 11 years later, at the Universal Exposition of 1878, the Champ-de-Mars station was built for the occasion. The visitors included a certain R. Martial, who made this comment about the Gallery of Machines: “[…] soon, there will be only one possible trade left – that of mechanic”.

Games,

tales and images

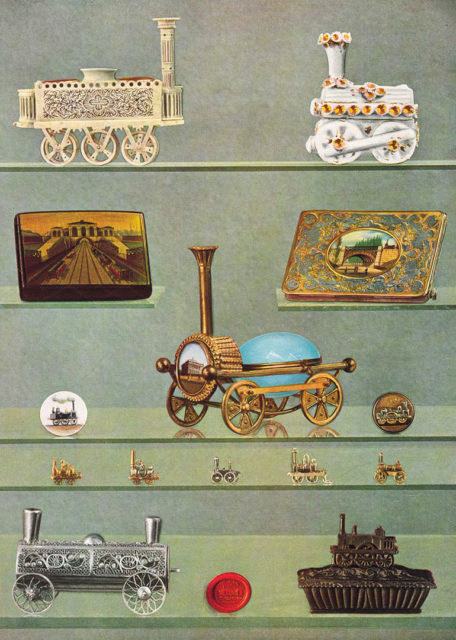

Trains nurtured an imaginary world that gradually spread to children. The “Jeu de l’oie des chemins de fer“, a railway board game created by Ernest Henry around 1855 that can be found in the Archives of Mulhouse is a perfect example of that phenomenon. On a board with squares bearing pictures of Epinal prints, players travelled from one station to the next. In 1872, a writer for La Semaine des enfants, a publication with amusing and educational pictures and writing, took pleasure in mixing historical periods. In a tale with renaissance notes and décor, trains made a discreet appearance. The writer reminded his young readers that in those days, one could only travel to distance places in extremely slow carriages. The train, a mysterious and noisy character, gradually became a subject of learning. When Jules Ferry made education in France free, secular and compulsory, the walls of classrooms and school books were gradually populated by locomotives. At the same time, companies like Märklin began to sell model trains. With toy trains and deluxe models, play and learning went hand in hand.

Learning

about the railways

While the 19th century was the age of scientific popularisation, the diversity of trades involved in the railways made companies organise their learning methods. At the international railway conferences organised in Milan in 1887 and then in Paris in 1889, the need to create special educational institutions was pointed out. Teaching of geography, physics, arithmetic and French were supplemented by technical learning in industrial drafting, cabinet making, boiler work and forging. The mastery over teaching materials and models became a prerequisite for the future career of young railway workers. Signal models and other masterpieces made by apprentices form a significant body of this part of the railway heritage and can be found at the Cité du Train.

Celebrating

the railways

50 years after the inauguration of the line between Paris and Saint-Germain-en-Laye, gaily draped platforms appeared in the Bois de Vincennes. On 22 May 1887, dove releases and concerts marked the commemoration. In spite of the bankruptcy of the organising company, that international event did however enable the writers for Journal des Débats to “browse through the old collection” of the daily and remind readers of a historic episode that could have been forgotten.

Folklore

and landscapes

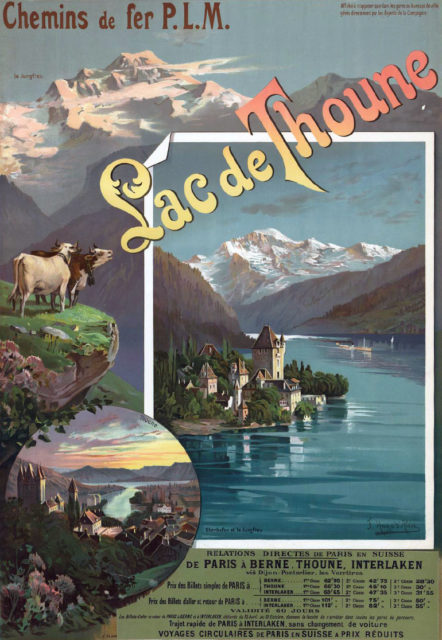

Railways were at their peak in the second half of the 19th century. In a few decades, railway transport had secured a lasting foothold in the day-to-day lives of a large number of people in France, as railway workers or regular users. Indeed, trains, combined with trams and cable railways, allowed people to go ever further, deep within mountain ranges or up to the sea.

Railway companies, which helped develop tourism, tried to be more creative than the competition when it came to promoting their destinations. Posters appeared in stations. These were brightly coloured and followed a recurring model, with at the centre, an idyllic landscape, sometimes with someone dressed in the local costume or what it was believed to be. The name of the company was stated in bold, most commonly with insets indicating the affordable cost of fares.

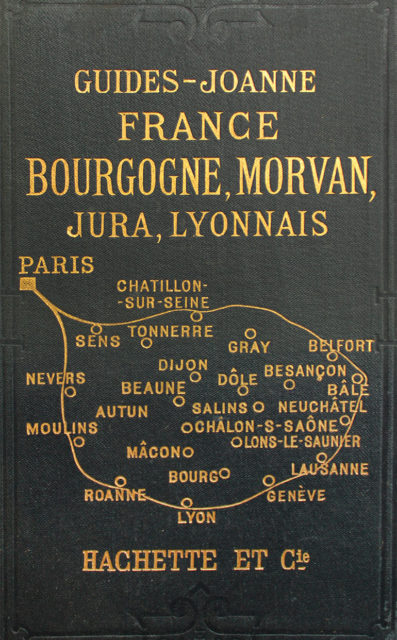

Later on, tourist brochures and guide books published by rail companies turned these organisations into recommenders of cultural practices. Joanne Guides, which were already sold in the railway bookshops managed by Hachette, made people want to travel. In 1872, when the Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits was founded, the picturesque was replaced by the need for a change in scenery.

By the dawn of the 20th century, railways had become a means of transport firmly rooted in the daily life of people across France. The inauguration of Orsay station in Paris in 1900 renewed the city landscape. Because unlike exhibition pavilions, these buildings were designed to last. With every new exhibition, the total length of tracks dedicated to railways grew significantly.

At the foot of the Eiffel tower,

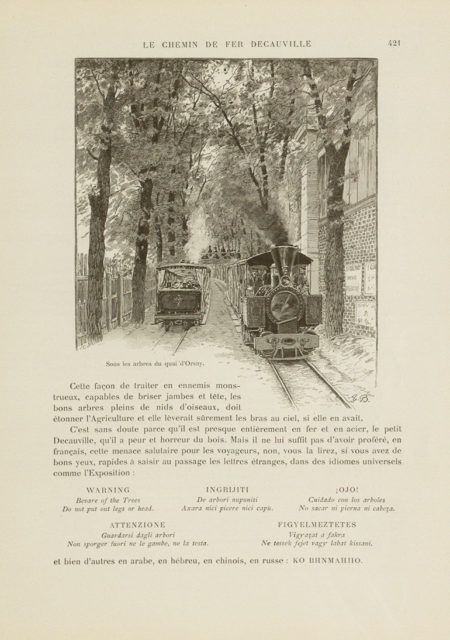

the internal railway

But while the [Eiffel] tower and its surroundings bring up the idea of an untidy and colourful heap of toys, it could be said that it is precisely why the exhibition has this jovial, cheerful and childish side, which makes life a holiday during which people succeed in putting away the chores of existence and the penitence of destiny. Those were my thoughts when I saw the successful reception enjoyed by the little narrow-gauge “Decauville” train as it is called, which – just look at it as it goes by – is a toy that actually works”.

– Emile Goudeau, 1889, in Revue de l’Exposition universelle de 1889

At the exhibition of 1889, class 61 dedicated to railway equipment was placed in two main galleries supplemented by four large spaces. Tracks and turn tables could be found there. Along the Avenue des Suresnes, part of the internal system known as the Decauville railway served restaurants and pavilions. With a three-kilometre length, this structure designed by Adolphe Alphand played a crucial part in the discovery of the exhibition. Engravings, postcards and photographs published in that year clearly shown the success of the narrow gauge system. The Decauville railway was used by foreign visitors, and thus demonstrated its efficiency and drove the fashion of the “mini train”, which is even today very popular with visitors to the Cité du Train.

In the eyes of Maurice Bixio, who wrote the introduction to the Notice sur l’Exposition centennale des moyens de transport of 1900, “The 19th century is the age of the most colossal development of means of travelling, within a town or a country, or even across the world.”.

Retrospective museum of 1900

In 1900, not far from the water tower of the Champ-de-Mars, in the Transport pavilion, class 32 devoted to railways and tramways opposed body work, saddlery, commercial navigation and balloons. The engineering elements were supplemented by paintings, engravings and photographs. In contemporary writings, the term “retrospective museum” was thus used on several occasions. In that context, it was specified that the model of the first locomotive with a fire-tube boiler of the Saint-Etienne to Lyon line was “obligingly” loaned by the Museum of Arts and Crafts. Nearby, on the picture rails between metal frames, show windows and frames were numerous. The aim was thus to “form a whole that is more appealing to the eye” and to “interest the public, because of its amusing and educational aspects alike”. 100 years before the publication of the Museums Act of 2002 and its article L. 410-1, the concepts of “knowledge, education and enjoyment” of the public were recognised.

The Vincennes annex

But the Champ de Mars was not large enough to accommodate all railway equipment. Propositions came in from a number of countries and ways had to be found to receive all the exhibitors. That led to the building of the Annex in the Bois de Vincennes, including among others a BB 1280 or “Bo-Bo”, the first electric locomotive, a model of which is today on display at the Cité du Train.

The wind cutter, an industrial fantasy

“I was in love with twelve steam locomotives. These delightful engines from 1905 were already aerodynamic. These were the magnificent wind cutters from PLM. They are famous in the history of railways. They are listed among the most harmonious locomotives that have ever been built, and they have had a definite influence over my entire life. I would prowl around the depot, and I soon befriended the workers. I would bring them Caporal cigarettes, and sometimes cigars.”

– Raymond Loewy, Never Leave Well Enough Alone, 1965

1900. Research in aerodynamics began to be applied to the world of railways. The wind-cutter nose of the C145 locomotives from PLM, was a sign of that movement.

In 1965, the tribute paid to it by the famous industrial designer Raymond Loewy in his book Never Leave Well Enough Alone raises these pieces to the status of true industrial design objects.

photograph: M. Lamarche, Cité du Train collection

“It would be a mistake to end these lines without saying a word of the general wishes of visitors as we heard them. The retrospective exposition of modes of transport was indisputably a very great success, and we heard, time and time again, regrets that a permanent museum, which could be interesting, has not yet been set up. ”

– Maurice Bixio, Introduction à la Notice sur l’Exposition centennale des moyens de transport, 1901

This Maurice Bixio quote is a reflection of heritage concerns from the very beginnings of the railways, and confirms a need: that of preserving and showcasing the railway heritage, a sign of technical progress, artistic inspiration and collective history. 75 years on, while the older members of society remember 1900, the young were dreaming of the year 2000.