The railway line between Mulhouse and Thann was inaugurated on 1 September 1839. 130 years later, in 1969, Mulhouse was selected as the future home of the French Railways Museum.

A railway

show

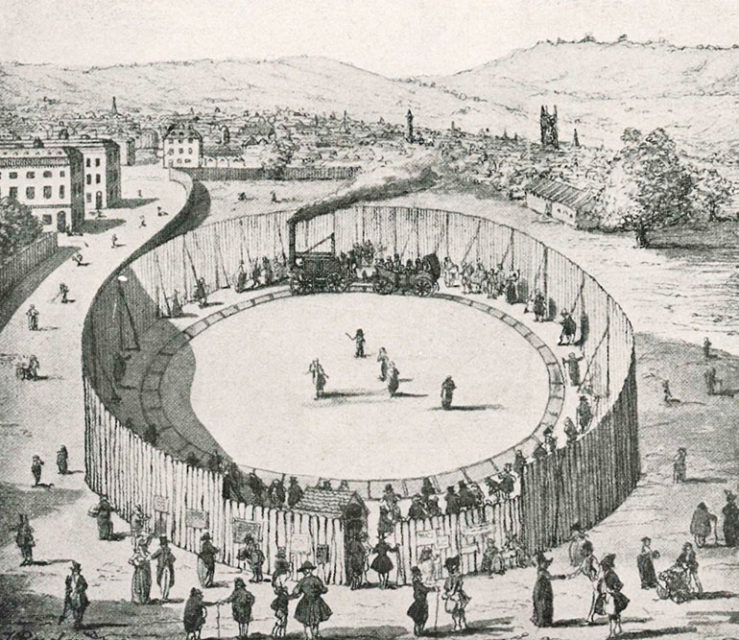

Where does the history of railways start? While one may be tempted to go back in time to the first sledges used in ancient Egypt, to the first rutted Roman roads or the wooden tracks of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the 19th century will remain the golden age of railways. Catch Me Who Can may be identified as the first demonstration steam locomotive. This four-wheeled machine created by Richard Trevithick in Britain was presented to public in London in 1808. That steam machine ran on a 200-metre long circular track and reached a speed of 20 km per hour. The large crowd were admitted to the novel “steam circus” for a price of five shillings. While the most daring enjoyed a turn on the single carriage, the inventor, on the brink of ruin, was sure of one thing: the ride was a harbinger of what would eventually become one of the greatest inventions of contemporary times: that of rail transport.

“A small sketch

of history”

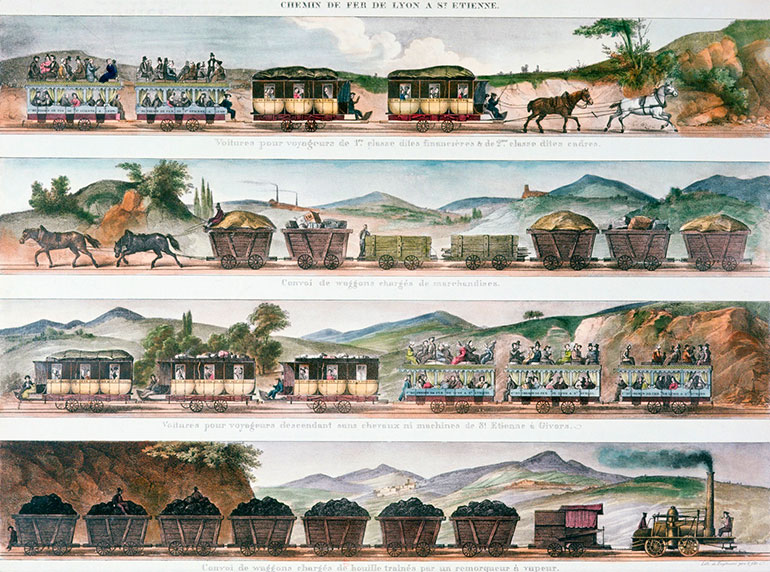

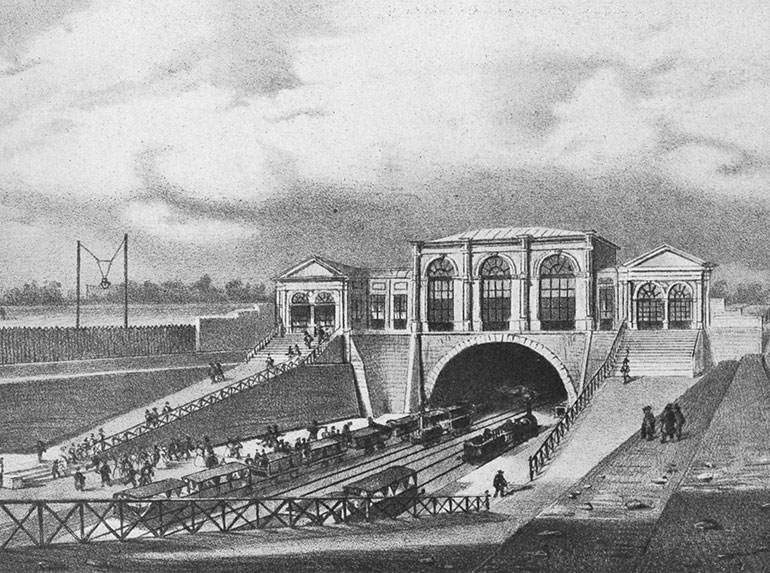

Founded in 1833, Le Musée des Familles, Lecture du Soir aimed to provide a “complete lesson of familiar, amusing and varied education for all”. This richly illustrated periodical was intended for a wide readership and one of its first articles was devoted to railways. After starting out with the indication that railways are still “not well known in France”, the writer describes the development of goods transport by rail using two examples: the British line between Manchester and Liverpool (1830) and that in France between Saint-Etienne and Andrézieux (1827). Picturesque engravings supplemented by technical diagrams gave subscribers an opportunity to discover what was said to be a developing mode of transport. Indeed, while England had already inaugurated its first passenger line between Stockton and Darlington (1825), work was under way in France, particularly led by the Séguin brothers.

The mystery

of movement

“It is sad to think that out of the thousands who travel every day from Paris to Saint-Germain, no more than twenty have taken the time to study the mystery of the movement that is carrying them, and are capable of speaking of it with any clarity. […] Could the authorities not do something to stimulate and encourage public curiosity in this area? Every time an important new machine is accepted by science and industry, would it not be of use to give the public an explanation, every Sunday, in a special venue, such as the Conservatoire des arts et métiers?”

Le Magasin Pittoresque, 1837

1835. For the first time, the Academy of Sciences published weekly minutes of its meetings. That publication, which was driven by François Arago, provided its readers with a precise review of current science news and debates. Eight years after the start of the line between Saint-Etienne and Andrézieux in 1827, these documents reveal the discussions within the scientific community. While treatises devoted to steam grew in number, they were however reserved for a select few.

Thus, in 1837, after the inauguration of the first French passenger line between Paris and Saint-Germain-en-Laye, a journalist writing for the Magasin Pittoresque lamented the continuing ignorance of the public when it came to the working of steam engines. To remedy that, he defended the use of “public explanation” sessions at the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers.

A place in the

conservatory

The Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers was founded in 1794 by Abbé Grégoire, and is a repository for a rich collection devoted to the railways. In his book published in 2007 named L’amphithéâtre, la galerie et le rail, Lionel Dufaux reminded readers that the first railway-related acquisition dates from 1824. A study of the inventories, catalogues and stock-taking documents dating from the 19th century also shows that the railway collection developed significantly under the July Monarchy. In 1843, writers for the Magasin Pittoresque thus described their tour of the establishment: within the great gallery, models of rails and cutaway views of locomotives at 1:5 scale showed how steam engines work. Ten years later, on 28 January 1853, in correspondence that was brought to light by Lionel Dufaux, Théodore Olivier, former director of the museum, stressed the main issues relating to the exhibition of life-sized rolling stock. He said: “[…] in a few years, the whole of Paris would not suffice to house all these new models that some of my colleagues dream of.”

A railway in

Alsace

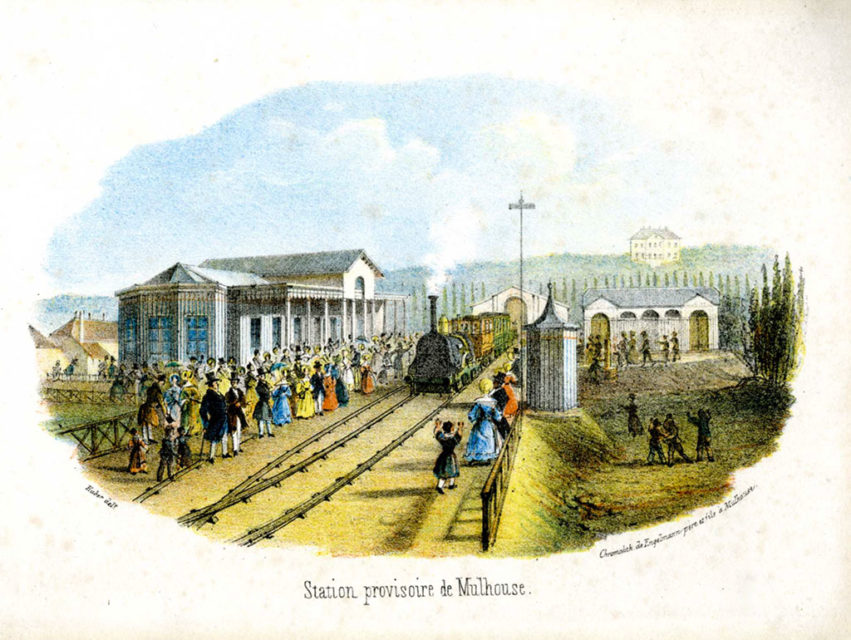

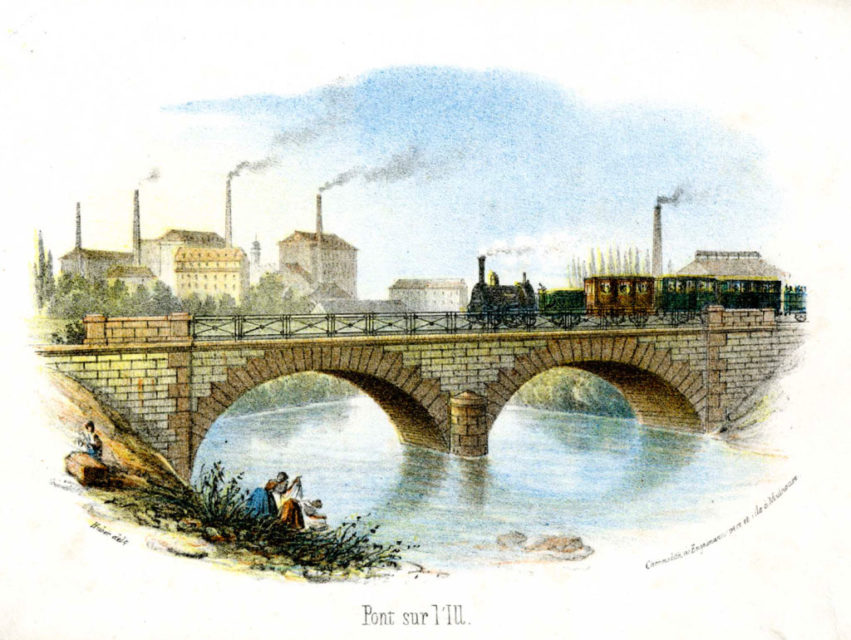

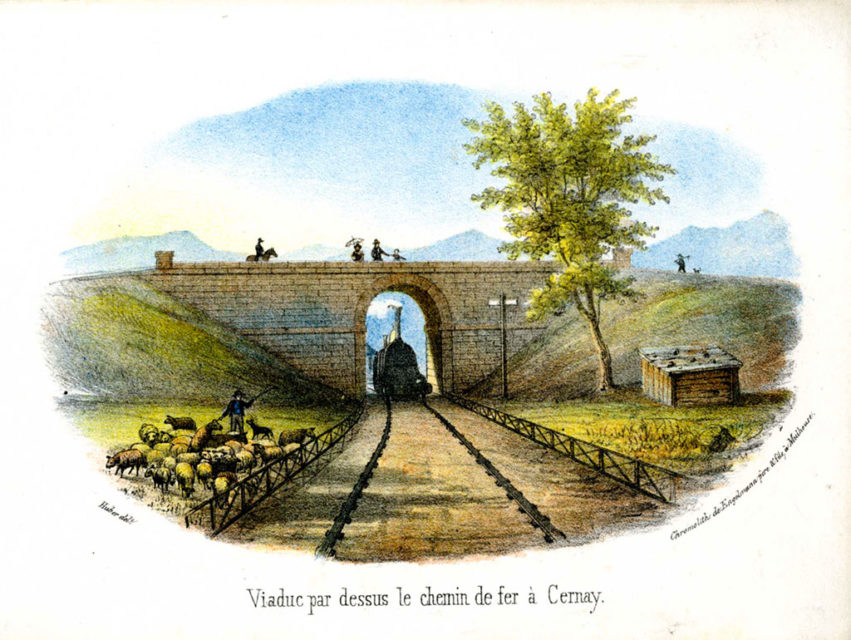

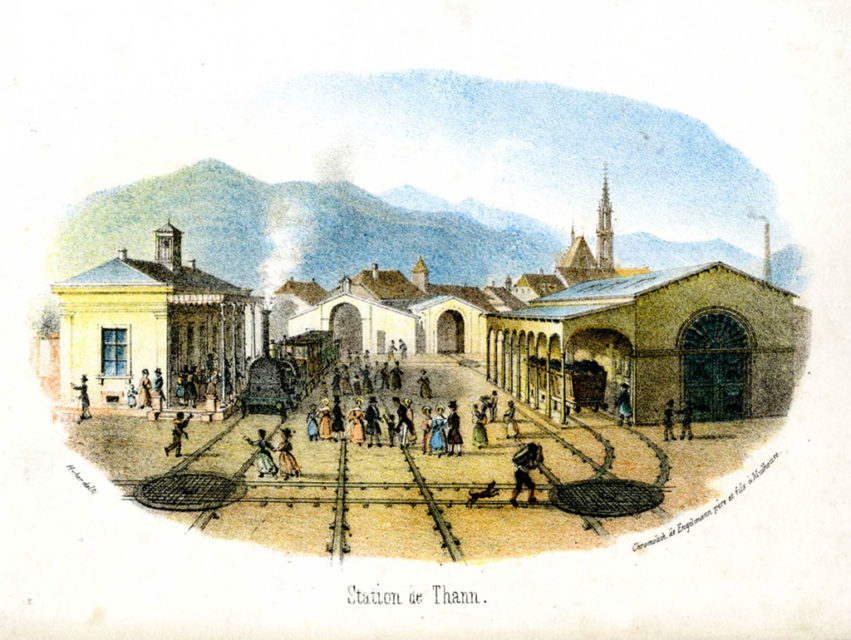

While the institution in Paris continued to add to its railway collection, the railway came to Alsace. In 1839, the inauguration of the Mulhouse-Thann line marked an important stage in the development of passenger transport. The event, which drew a large crowd, was the culmination of an ambitious project promoted by Nicolas Koechlin. Top hats, crinolines and parasols came out in a setting that brought together the Vosges mountains and engine smoke. The train was led by the Napoleon locomotive made by André Koechlin et Compagnie (forerunner of the Société Alsacienne de Constructions Mécaniques), which soon became a symbol of the know-how of Mulhouse. In 1841, Strasbourg-Basel became the first international rail link. Over a century later, these historic episodes would contribute to the birth of the French Railways Museum in Mulhouse.

– Act of 11 June 1842, after 1842, Dollfus collection stored at the Cité du Train

French Act of 11 June 1842

“Article 1

Act relating to the establishment of trunk railway routes

A railway system shall be established, directed, 1 From Paris

To the border with Belgium, through Lille and Valenciennes;

To England, through one or more points on the channel coast, to be determined at a later time;

To the border with Germany, through Nancy and Strasbourg;

To the Mediterranean sea, through Lyon, Marseille and Cette;

To the border with Spain, through Tours, Poitiers, Angoulême, Bordeaux and Bayonne;

To the Ocean, through Tours and Nantes;

To the centre of France, through Bourges;

2 From the Mediterranean sea to the Rhine, through Lyon, Dijon and Mulhouse;

From the Ocean to the Mediterranean, through Bordeaux, Toulouse and Marseille.”

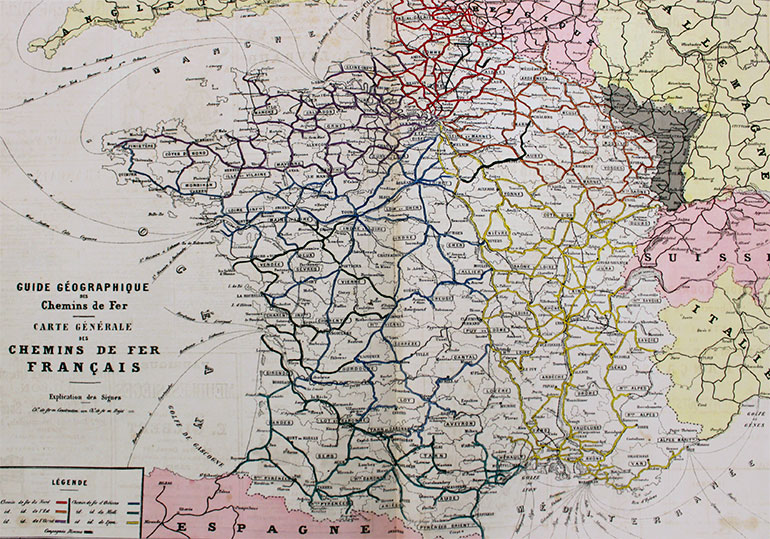

Promulgated by King Louis-Philippe, the Act of 11 June 1842 redefined the map of France. In its nineteen articles, the law established the future railway network from a central point: Paris. Along with the confirmation of that configuration, which was called the ‘Legrand star’, the government set out a number of financial and policy arrangements. For example, if a company agreed to pay for the construction of a line, the government agreed to give it a monopoly on the operating area. While the law led to increased speculation and the coming of players such as Rothschild’s Bank, it also helped the growth of the main railway companies, which continued to operate till the SNCF was founded in 1938.

Early

companies

As the months passed, the railways spread their web along the roads, through forests and across rivers. Across France, railway lines mushroomed, carrying goods and passengers. As part of that unprecedented geographical, technological and social revolution, businesses emerged, grew, disappeared or joined forces. A review of the Journal des chemins de fer et des progrès industriels, published in 1842 for the first time, gives an insight into this far-reaching phenomenon. By the end of the Second Empire, six main railway companies dominated the market. These were Compagnie du P.O. (Paris-Orléans, 1844), Compagnie du Nord (1845), Compagnie de l’Est (1845), Compagnie du Midi (1852), Compagnie de l’Ouest (1855), and Compagnie du P.L.M (Paris à Lyon et à la Méditerranée, 1857). They were very often modelled by a colour code covering every centimetre of the map of France, and were the bearers of an extraordinary tangible and intangible heritage.