EXPOSITION – STOP – WISH YOU EVERY SUCCESS

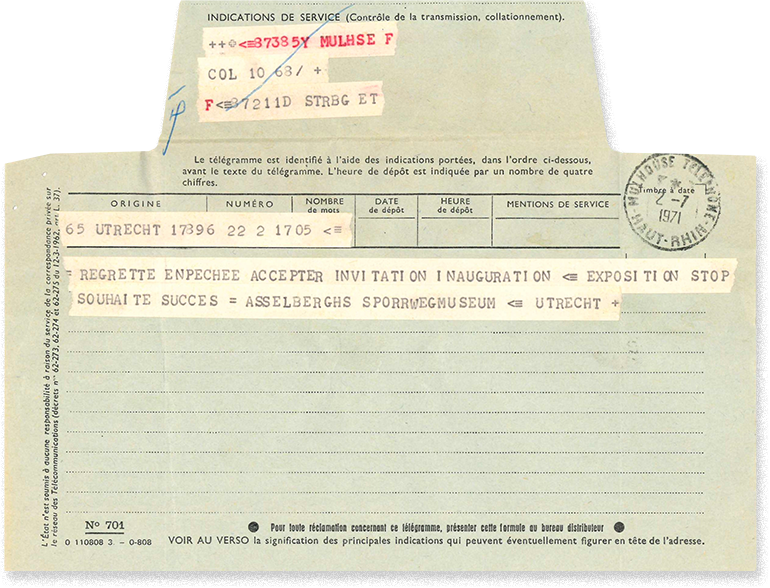

In January 1970, in one of the pages of Towards a French Railways Museum, Michel Doerr and André Portefaix proposed a panorama of European railways museums. Their findings were clear: while Mulhouse was getting ready to open its museum, cities like Hamar, York, Nuremberg, Madrid, Copenhagen and Belgrade already had such institutions. Throughout their museum career, Jean-Mathis Horrenberger and Michel Doerr tirelessly devoted themselves to exchanging notes with them. For example, the Utrecht museum was invited to the inauguration of the half roundhouse in 1971.

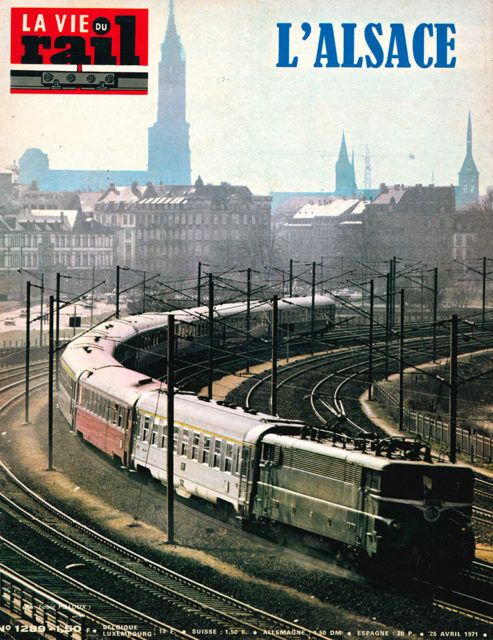

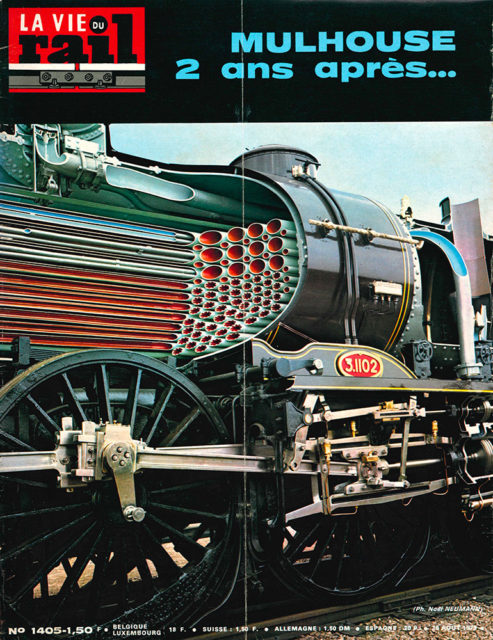

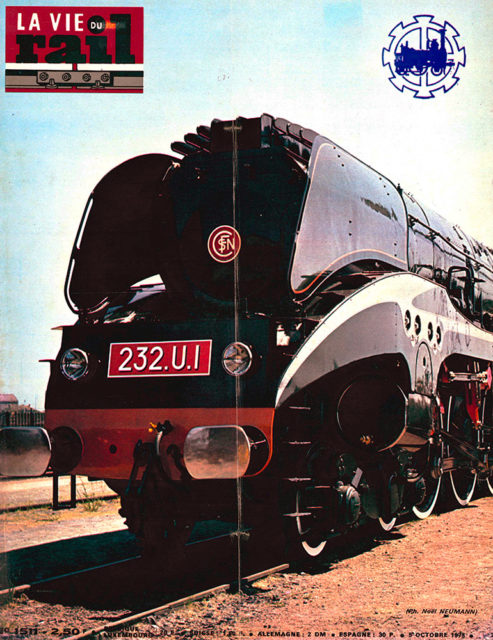

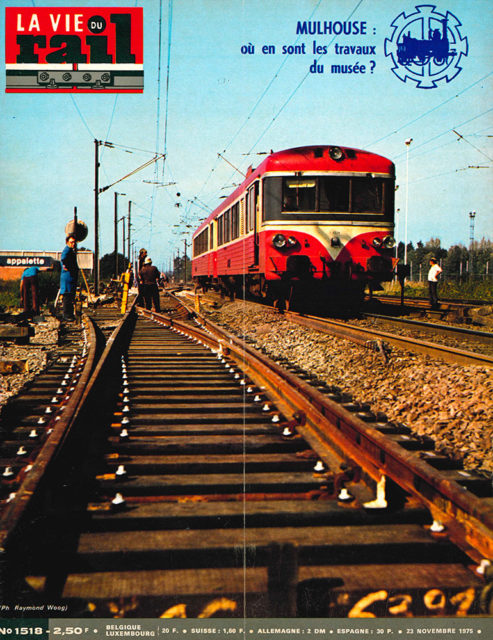

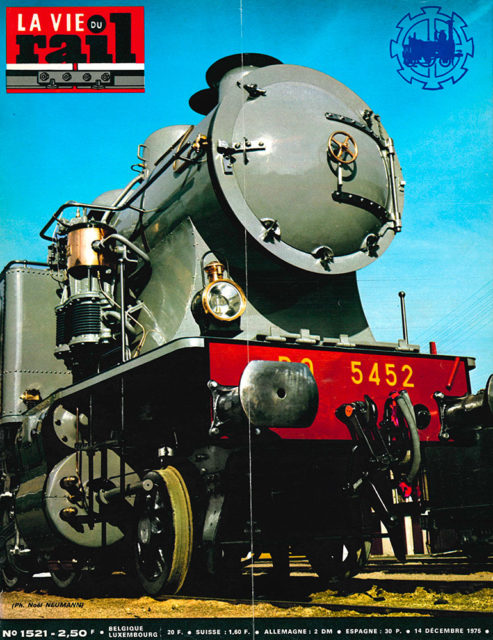

While life went on at the half roundhouse, local, national and specialised media were already devoting articles to the future permanent museum. Like a portrait gallery, the covers below take you back to the chronicles of the work being undertaken.

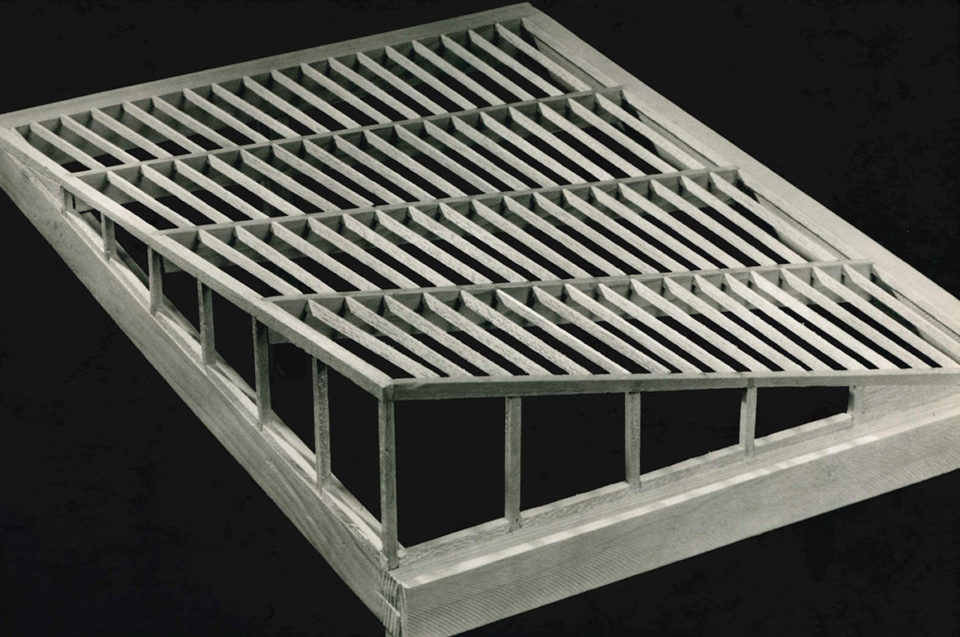

Wood and glumlam

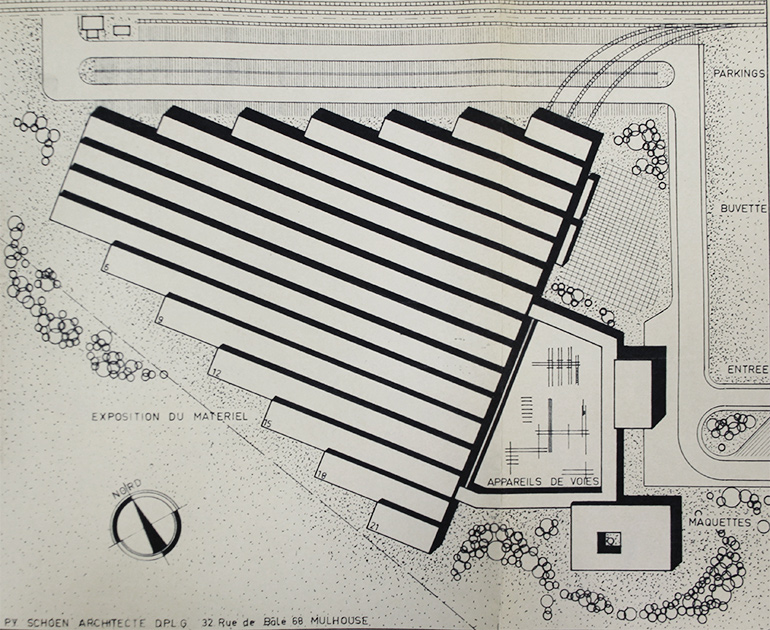

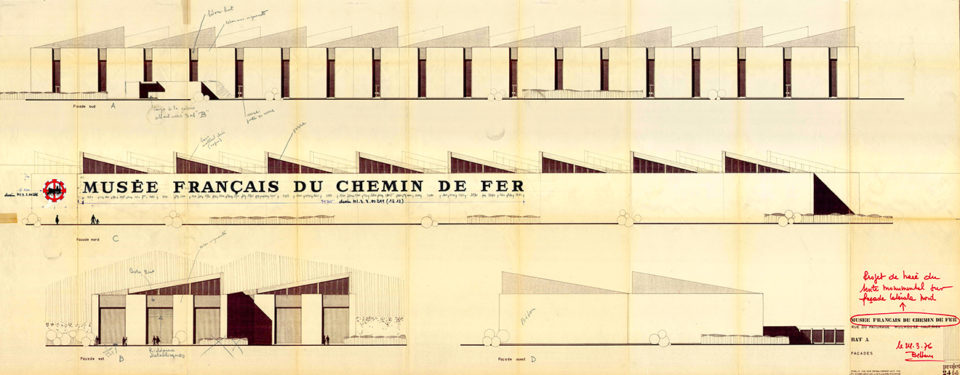

From the beginning, the architect Pierre-Yves Schoen was informed by Jean-Mathis Horrenberger of the planned French Railways Museum in Mulhouse. He became a major player in its history. In October 1967, a meeting organised by the Committee for the creation of a French Railways Museum in Mulhouse set out a certain number of points. First of all, land would indeed be provided by the City of Mulhouse in the Mer Rouge district for the permanent building. The plans of that structure, which were already published in a newsletter of SIM, would include 35 tracks to display over 100 items. They would be supplemented by an area devoted to model trains and components. The idea of combining that early part with the creation of a museum devoted to fire fighters was also defended.

While some members and visitors were already nostalgic for the genuine railway atmosphere that had been made possible by a roundhouse, only the construction of a new building out of nothing could organise the flow of visitors and allow an extension of the collection. That setting, described as “unusual” by the architect, gave the pieces on display a more museum-like feel, and offered the possibility to create a large car park and a restaurant. While the construction of such support amenities was not out of the ordinary, that was not so of a museum devoted to trains. In May 1976, Pierre-Yves Schoen wrote an article in the Revue Générale des Chemins de Fer and explained that the first step would be to think of how the equipment would be brought to the site. That meant that the museum had to be built by a railway track, ideally supplemented by turntable, or transfer equipment. These solutions were found to be too expensive and were abandoned. The building was to be located on a triangular plot of land, so as to connect its internal tracks to the Strasbourg-Mulhouse track using a carefully calculated bend radius.

“To those constraints relating to the building site, were added those that I thought I knew but whose significance I had barely discovered. For instance, constraints due to the subject of the project: railways. To display a vehicle, you need 22 m x 9 m, that is above 200 m². In order to let the object “breathe”, the ceiling height has to be about 9 m. There must be enough light in the room, to allow photography. Visitors must get to see everything, top, bottom and sides, but must not be able to “touch”. Those are the broad outlines of the requirements for the exhibition room.”

– Pierre-Yves Schoen, document typewritten before the summer of 1971, Cité du Train collection

Inside the building, the requirements of conservation and display were also painstakingly studied. The constraints imposed by the size of trains were supplemented by those for photography. Even before the age of smartphones and social media, it was already obvious that visitors would want their souvenir photographs. The space therefore had to be bright and large. The “cost-effective and elegant” solution. The materials were selected with care: steel, wood and concrete were preferred. For example, the arcs that support the roof were designed using the principle of glulam wood.

In a letter sent in November 1969 to Michel Doerr, Pierre-Yves Schoen described this method as ideal, since it allowed “large spans with no support points, freedom to locate posts and fasten walkways at any point of the frame.” The main posts and beams were made in reinforced concrete. The façade was to be finished in Rhine pebble dash.

“This is the future location of THE FRENCH RAILWAYS MUSEUM”

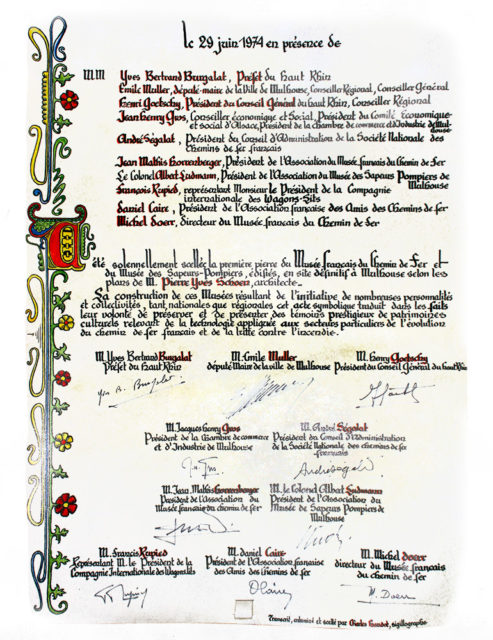

The laying of the first stone, marking the official start of building work, was a high point in the history of the museum. The event, organised by the local contractor Savonitto, consisted firstly in clearing away, cleaning and top soil stripping. A block made up of a cast concrete stone was also made. Inside it, a piece of parchment for posterity was inserted during the ceremony of 29 June 1974. The document, which was signed at a meal organised at the restaurant in Mulhouse zoo, was found during work in the 2000s, and so reached us safely.

Publications about

the collection

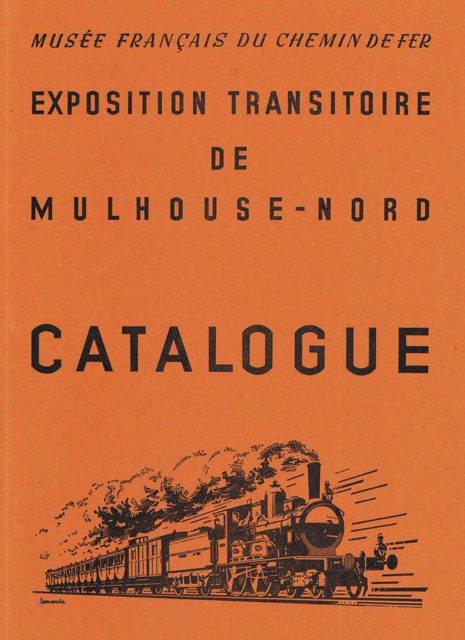

In April 1975, the catalogue of the collection in the temporary exhibition of Mulhouse North was published. Richly illustrated with drawings by Michel Lamarche and E.A. Scheffer, the collection was characterised by original graphics aimed at highlighting the collection. It also provided an opportunity to briefly outline the history of railways and that of the museum. The concise text demonstrates the intention of addressing a wide public. Purchased by the Cité du Train in 2019, a version signed in 1975 by Michel Doerr is a nod to the future. The former Director was certain that the document would in a few years be part of the history of Alsace.

“In France, people believe that the public are not very open to issues relating to railways, which, they believe are an instrument of the past; however, when you see visitors crowding to have a close-up view of the equipment displayed, climb into cabs, pull the governor and operate the controller, one may ask whether the same public are really uninterested or if their indifference is not actually the result of a lack of opportunities to satisfy their curiosity…”

– Chemins de fer, no 134, May-June 1945, p.70

“I will go with it to the museum…”

Almost thirty years later, in July 1974, in a letter to the founders of the museum, a member of the organisation asked when the locomotive 232 U 1 would be displayed. The writer could be reassured since the locomotive, a masterpiece of the engineer Marc de Caso, was being given a complete refurbishment by workers in the Thouars workshop, and would be visible in the future museum. The film above was first screened in November 1975, taking its viewers behind the scenes, showing a project that would last two years.

The 232 U 1 was scrubbed and painted, bearing a whole section of the history of railways and their museum. In 1976, under the brand new structures of the new museum and thanks to the technical support of SNCF, the machine was put into motion without moving. Nearly fifty years on, this animation can still be seen in the museum.

Station to station

1976. The title track Station to Station on side A of the David Bowie album starts with the sound of a running train. Many miles away, between Mulhouse-North and Dornach, that mechanical melody echoed symbolically. As part of the opening at 2 rue Alfred de Glehn, the last items of rolling stock were leaving the half roundhouse. The end of an adventure? Oh no! The start of a new chapter, and mainly the entry into the new decade: that of the 1980s.

In a letter sent on 20 May 1976 to André Portefaix, Michel Doerr expressed his thanks for the “marvellous photos” brought by Mr Naudot, which “provide extraordinary memories of this roundhouse we are about to leave”. Moving a bit closer to the Vosges, the French Railways Museum ceased to be temporary and became final. And between the now bare walls of the depot, these words could be heard: “Here we are, one magical moment, such is the stuff, from which dreams are woven”.