That is the number of visitors who discovered the temporary exhibition in the half roundhouse of Mulhouse North between its opening to the public on 12 June 1971 and its final move to 2 rue Alfred de Glehn in 1976.

Mulhouse,

trains on display at last

12 June 1971. 10 am The French Railways Museum finally opened its doors. 82 visitors were already there to see the temporary exhibition in Mulhouse North. That number kept growing over the day. And yet, the competition was fierce: the Le Mans race was starting with a bang on televisions across the country! Trains or cars, that was the question. As reported in L’Alsace in its issue of 13 June, two lorry drivers, Mr Frey and Mr Woelfel, happened to be the very first visitors, under the attentive gaze of Michel Doerr, in his blue raincoat.

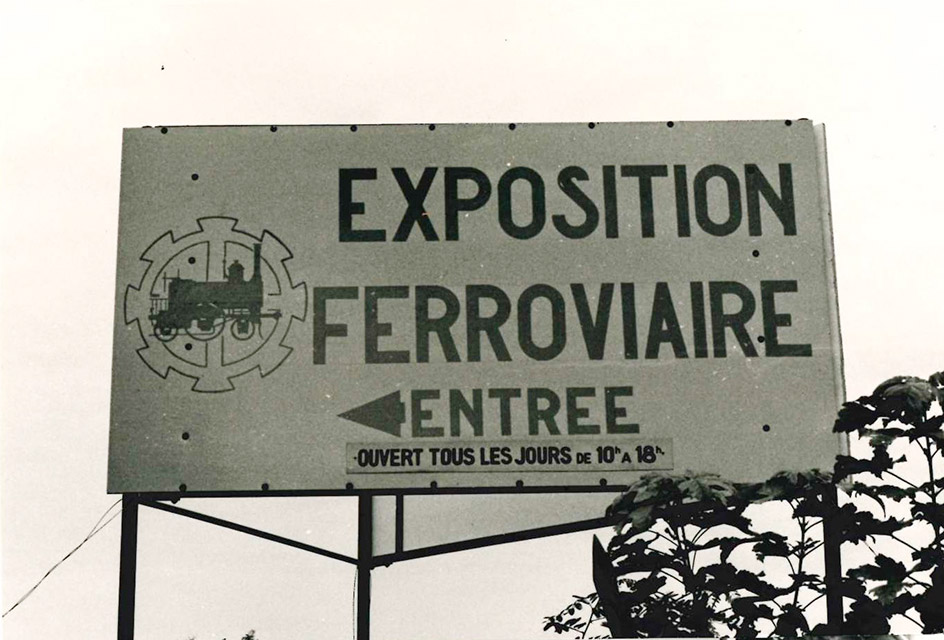

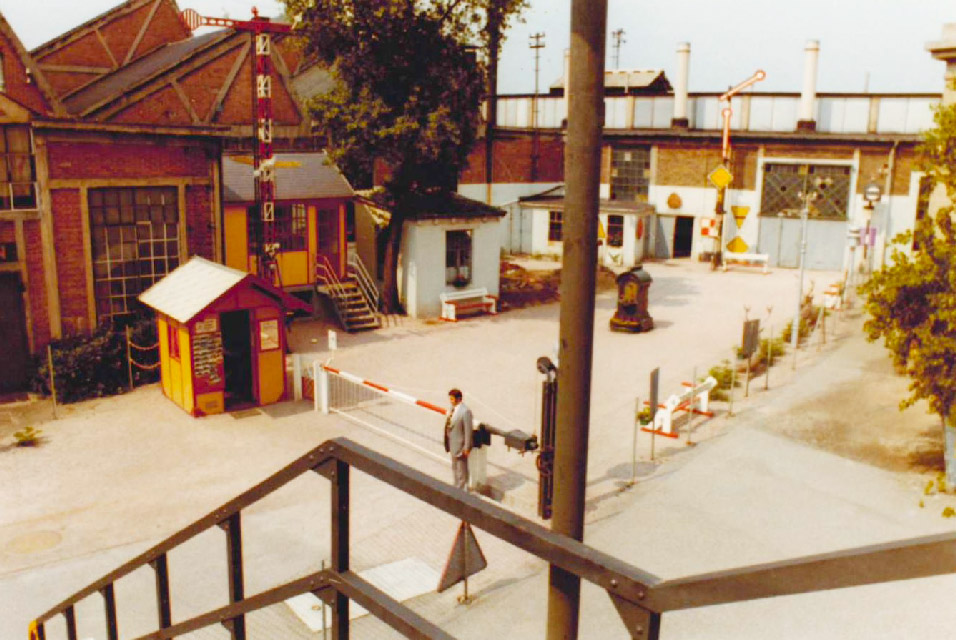

For some, the discovery of this new cultural amenity was an unprecedented experience. You parked along rue Josué Hofer or at the depot car park, and then took a footbridge over goods train tracks. In the distance, the half roundhouse announced its museum status in red capital letters to curious and resolute visitors.

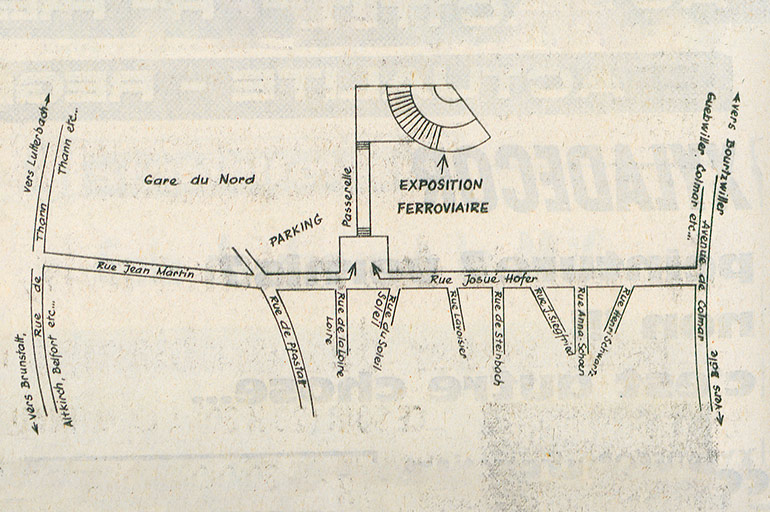

On 19 June, the newspaper L’Alsace pointed out that access was not easy for those who were unfamiliar with the Mulhouse railway scene. Another access map had to be published. That initial hiccup did not last long. The museum staff soon began putting out signboards, distributing flyers and working alongside the Mulhouse tourist office and the local, national and international press. For example, five months later in October 1971, 130 German journalists had already been to the museum. Even before it moved into its permanent home, the museum aimed to make its mark on the public mind.

000001

The first museum ticket (numbered 000001) was unearthed in a bundle of archives, and is now a precious relic. Beyond its symbolic aspect, it raises an interesting question: can an object about the history of a museum itself become a museum piece? One thing is sure, much thought went into the making of this little piece of paper, 5.7 x 3 cm. Its format, thickness, colour and fonts are as many nods to old railway tickets. It was punched at the entry to the half roundhouse, and immediately carried the visitor away into the world of the railways. In that regard, admission rates were a central issue and led to a number of discussions from the very outset. In the first museum newsletter published on 4 June 1971, the idea of offering concessionary rates for children aged 6 to 15 and free admission to members of the organisation was already floated. In November 1971, the second issue informed the members of the organisation that “at the suggestion of the City of Mulhouse, the decision has been made to create a special rate for all groups (of at least 10) of school children visiting with their teachers”. Over the years, as operating costs rose, the admission rates did eventually increase. Between 1971 and 1974, the full rate went from FR3 to FR5, and the concessionary rate went from FR2 to FR3. At the same time, the categories of visitors entitled to free admission grew. The employees of French railways and the CIWL were among them.

Care and

display

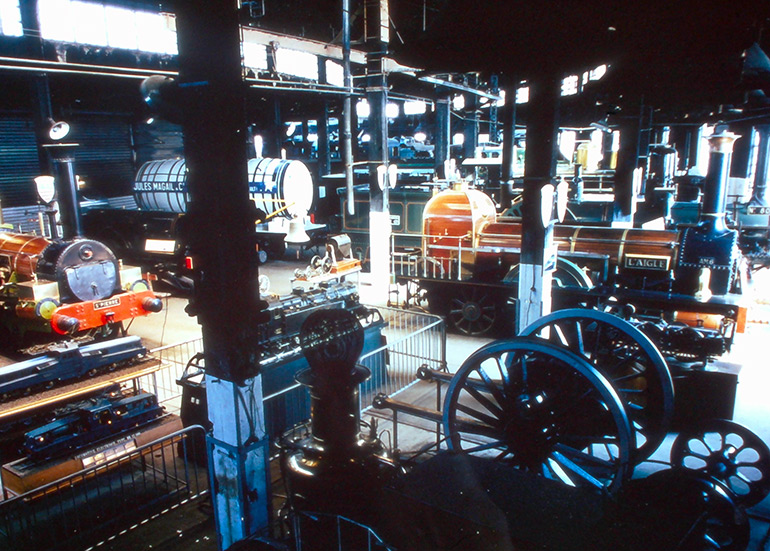

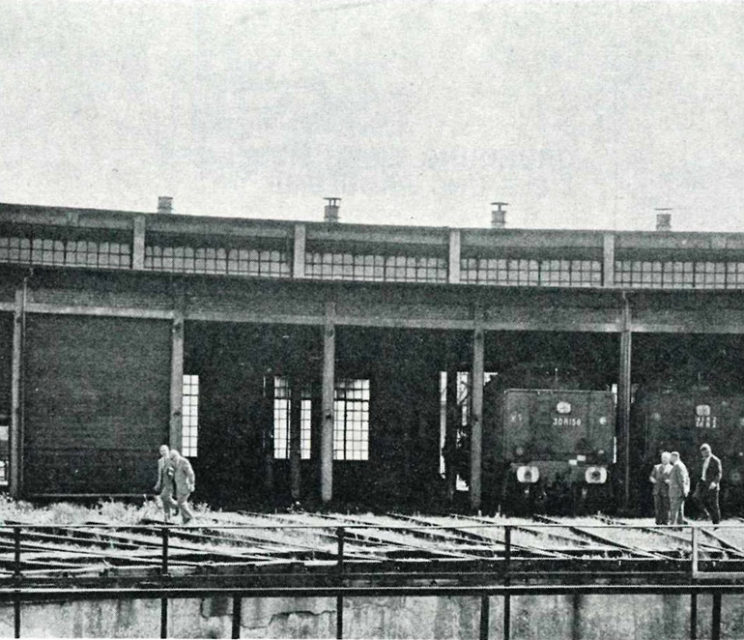

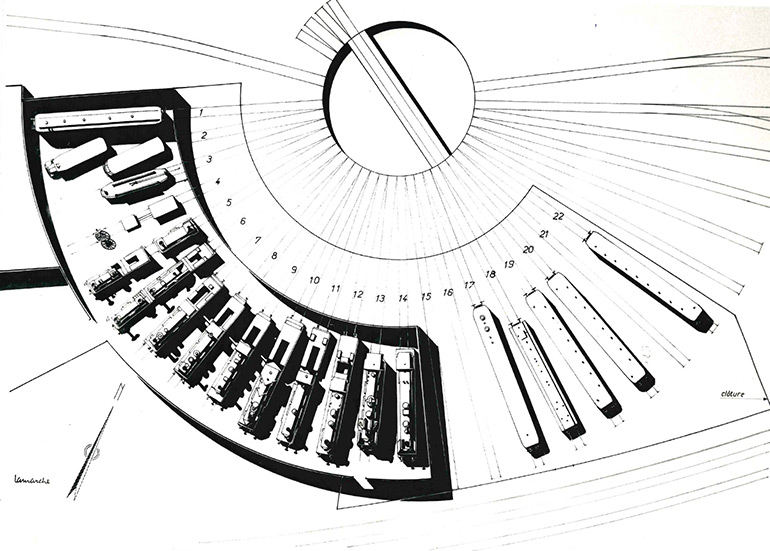

Once past the ticket office, visitors were asked to enter the half roundhouse A of Mulhouse North. The structure, built in 1923, was used for working on 141 R steam locomotives up to 1970. In September of that year, the electrification of the Mulhouse-Belfort line made it obsolete. Cleaned of its soot, the half roundhouse and its 14 tracks appeared to offer an ideal temporary solution. The individual metal curtains between the tracks and the turn table also kept the museum objects safe and secure. But as Michel Doerr pointed out in one of his letters, the new role of the building as a museum could only be fulfilled with some preliminary changes. The installation of a ticket office (former crossing keeper’s house) and a lavatory (inside a passenger carriage) were some of those changes. The museum was not just intended to house a “sample” of rolling stock, but also to put it on display for the public.

Caring for and displaying seem to have been the watchwords of the institution from its beginnings. Michel Doerr, who was keen to hire a team for maintaining the equipment, restated the need to have full-time employees, to staff the museum round the clock and round the year. In a handwritten note to Jean-Mathis Horrenberger, the Director calculated a need for 8 hours of weekly labour for each machine, that is to say 96 hours for 12”. Those employees were supplemented by guards, clerical workers, salespeople, cleaners and guides for school and other groups, which had begun to come in ever larger numbers.

“The main problem before us is that of hiring the employees that will be necessary for:

– adequately receiving visitors and supervising the museum during visiting hours, […] not forgetting merchandising, which would require the installation of stalls selling souvenirs, documents, postcards, slides and miscellaneous gadgets […]

– maintaining our large machines and the building. […]”

Michel Doerr in Musée Français du Chemin de Fer, special issue no 3 of the quarterly newsletter of the Société Industrielle de Mulhouse, 1971

Early rolling stock and partnerships

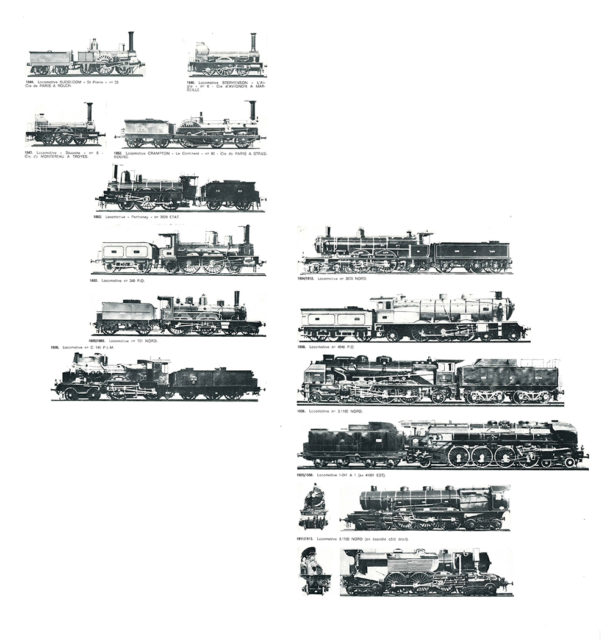

While some equipment was still being restored in the workshops of SNCF, other items were already onstage. That was true of the Forquenot locomotive, which came serenely into the half roundhouse in November 1971, hidden by protective polyvinyl. Spread over 14 tracks, the first rolling stock of the museum was listed a few months later in a document titled “Brief description of equipment displayed in the roundhouse (from left to right after entry).” For each locomotive, it briefly indicated the empty weight, drive wheel diameter and place of restoration. That early list also mentioned partnerships with AMTUIR and CIWL. The Diagram of locomotives that was put on sale provided a stylised overview of the profiles of each machine. The document below, published three years later in 1974, uses an aesthetic similar to that of natural history drawings . The collection was seen a living entity, which would continue to develop.

A museum that is the “only one of its kind”

In the writings contemporaneous with the temporary exhibition in Mulhouse North, the issue of museography was raised time and again. Indeed, the requirement was uncommon, that of exhibiting large objects in a manner that was both scientific and enjoyable. For Michel Doerr, the presentation also needed to be the “only one of its kind”, and “well spaced out”. The limited area available in the half roundhouse thus made it necessary for the museum designers to make difficult choices. Those were particularly imposed by preventive conservation issues. Some carriages, believed to be too fragile, were thus kept aside for the future final museum; that was particularly true of carriage A 151.

While steam locomotives may be displayed in a depot roundhouse, such a building is, however, a relatively inadequate shelter for significantly more delicate parts that require more careful maintenance. In view of conservation considerations, some antique carriages that have already been carefully restored in the workshops of Romilly have not been put on display in Mulhouse North. They will remain where they are for now, in better conditions (hall that is entirely sheltered from the elements, heated in the winter, with satisfactory humidity etc.).

– Michel Doerr in Musée Français du Chemin de Fer, special issue no 3 of the quarterly newsletter of the Société Industrielle de Mulhouse, 1971