Quatre-Mares

lives up to its legend

“[…] missing parts, to be reconstructed with materials that are not identical to the original ones (for instance, puddled iron is no longer made), finishes that have disappeared and old fabrics that are not available, markings that have been forgotten, decorations that are terribly expensive if an “identical” reconstruction were to be attempted; all this for an object whose fairly long life has not been without modifications and even complete reworking. Which of the successive stages must be kept for posterity?”

Michel Doerr and André Portefaix

“Vers un Musée Français du Chemin de Fer”, 1970

As the owner of the original collection of the museum, SNCF also provided its expertise in the area of restoration. From 1967, the Buddicom Saint-Pierre, an iconic locomotive dating from 1844, thus moved to the workshop in Quatre-Mares. Located in Sotteville-lès-Rouen in Normandy, the workshop, now a “technology centre” proved its status as the inheritor of that inaugurated during the July Monarchy by two British engineers: William Allcard and William Barber Buddicom. Over a century after it was designed, the locomotive got back its number 33, which was removed during the first restoration in the early 20th century.

As pointed out by Michel Doerr and André Portefaix, chief engineer of the Equipment department, restoration must be thoroughly documented in advance, and must in theory put the train back as accurately as possible into its original condition. But the doctrine was not so easy to apply in practice…

The “gem” of

Romilly-sur-Seine

Trains as works of art. That could be title of the note sent by Michel Doerr to Jean-Mathis Horrenberger on 17 February 1969. In this letter, which uses the vocabulary of jewellery, the future director of the Museum described the progress of restoration work on the Class A 151 Nord first-class carriage. Praising the workers of Romilly, both active and retired, this letter also gives an idea of the diversity of the know-how required for restoring some rolling stock. Carpentry, cabinet making, boiler work, painting and textile work are some of the trades required for restoring this carriage to its past glory, an incarnation of the Second Empire style.

“A true gem […]

certainly and by far the finest of the restorations completed until now […]

“loving” supervision of the hands that restored it […]

wide temperature variations that are harmful for conservation […]

takes up its place in Mulhouse in an appropriate “temple”[…]”

– Quotes from the note sent by Michel Doerr to Jean-Mathis Horrenberger on 17 February 1969

Napoléon

and the mill

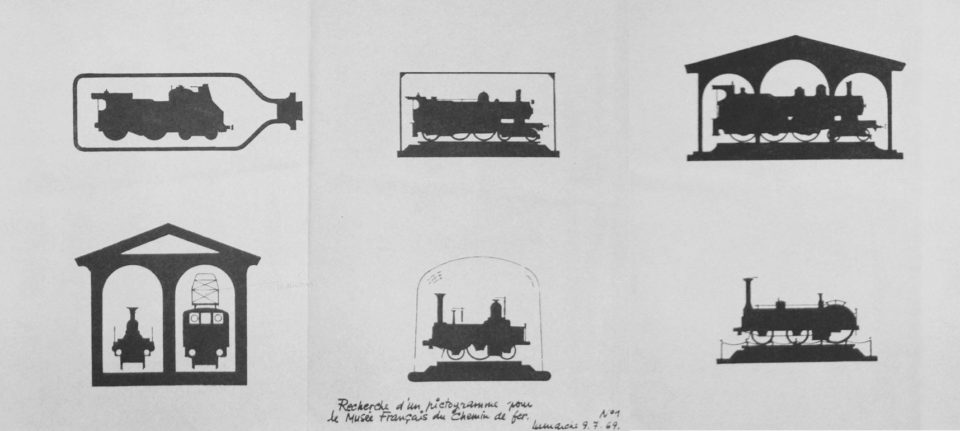

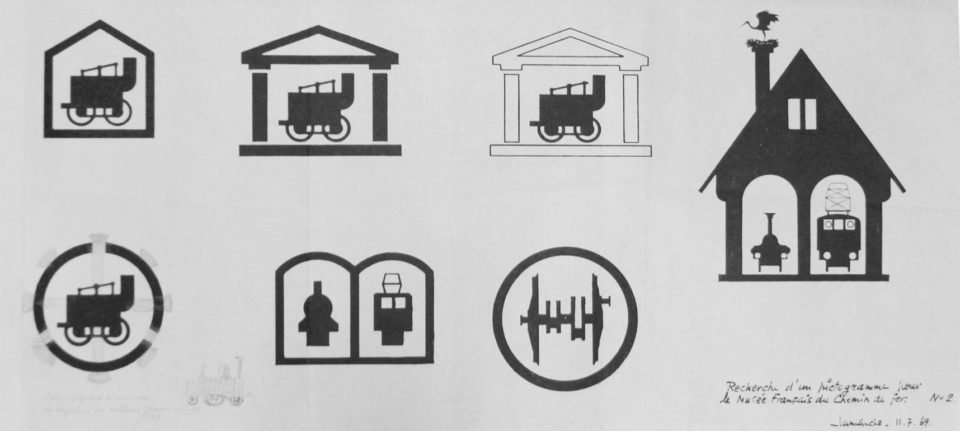

What would a museum be without its collection, its building, its staff, its visitors and also its logo? In July 1969, the railway painter Michel Lamarche got to work. His preparatory sketches show his wish to put together the three constituent elements of the future museum: trains, the building and Alsace. Presented by Michel Doerr in October 1969 at the constituent assembly of the Association pour le musée des chemins de fer de Mulhouse (AMCF Mulhouse), the pictogram was simplified. Before the scarlet wheel of the mill, famous as the emblem of Mulhouse, you can see a locomotive: the Koechlin Napoleon. The railways museum absolutely had to be in Mulhouse.

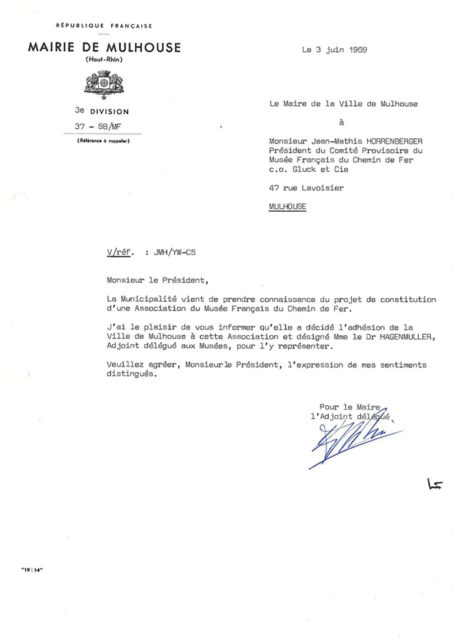

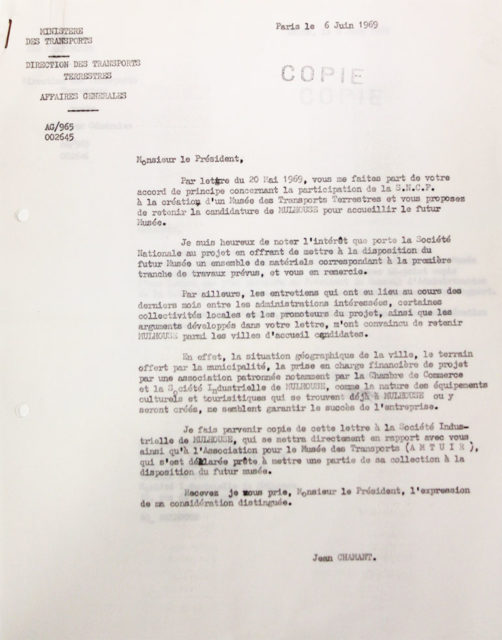

Formation of the museum organisation

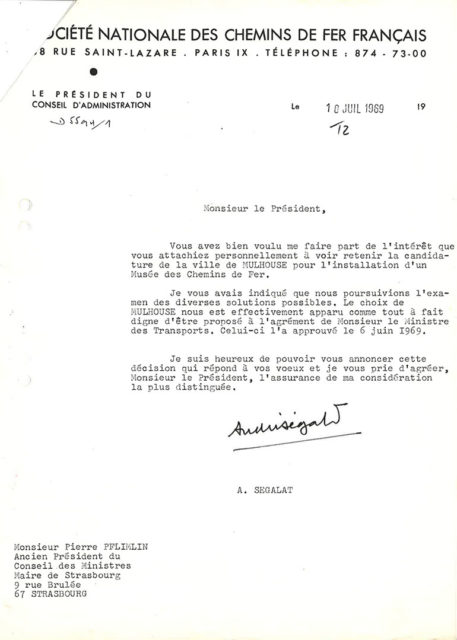

14 October 1969. The meeting rooms of the Société Industrielle de Mulhouse were buzzing. The city, SIM, SNCF, the CCI, CIWLT, the local fire fighters organisation and AMTUIR were at the presentation of the articles of the Association du musée des chemins de fer de Mulhouse. Jean-Mathis Horrenberger and Michel Doerr, the essential protagonists of this Titanesque enterprise, were officially appointed President and Director of the future establishment. The signature was the result of many solicitations and interventions on the local and national level, and simultaneously marked the start of a huge project under the architect Pierre-Yves Schoen: that of the final museum, which would be inaugurated in Dornach seven years later in 1976.

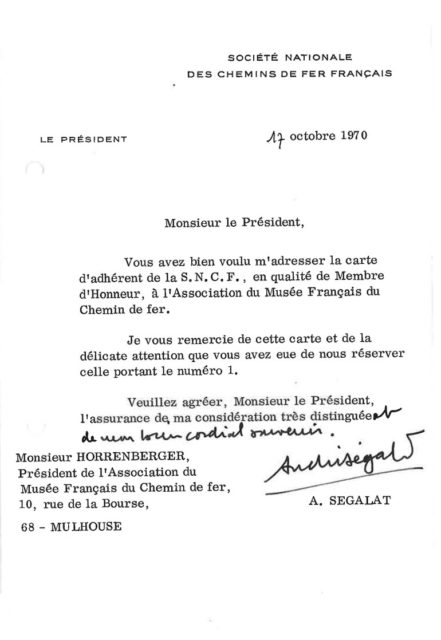

Number 1

Today, the museum contains equipment and objects provided by CIWLT, RATP, AMTUIR and La Poste, but SNCF is the owner of most of the collection. In October 1970, an honorary member’s card bearing the number 1 was sent to André Ségalat, then President of the company.