A refuge

in Chalon

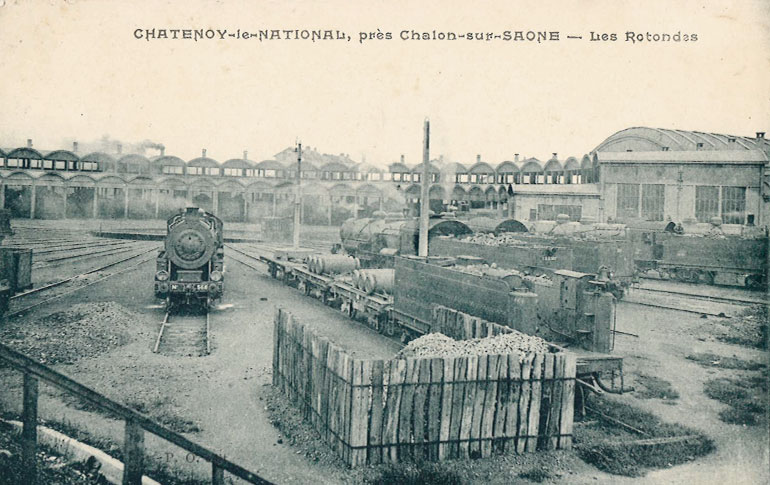

The demise of steam did not only affect railway employees who worked on board trains. It also resulted in a decrease, and in some cases in the conversion of the activity of railway workshops and depots. These were used to house equipment, and were complex architectural structures. Roundhouses, turn tables, pits, fuel magazines, water and sand are some of the elements that could be found in these buildings inherited from the early rail companies. That was so of the depot in Chalon-sur-Saône, which, in the early 1960s, was given a new function, that of conserving historic rolling stock that would move to the museum a decade later.

Genesis of an

inventory

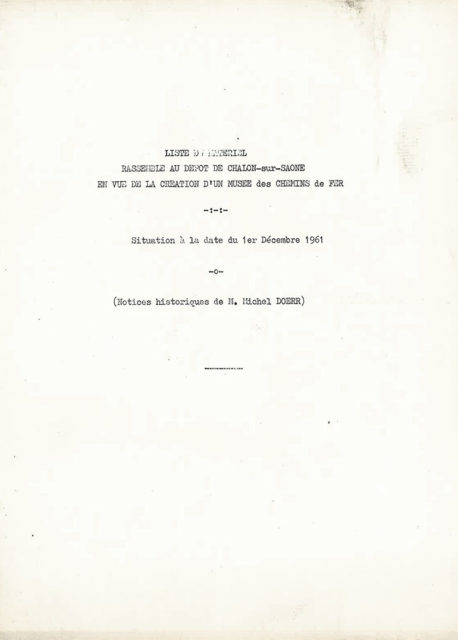

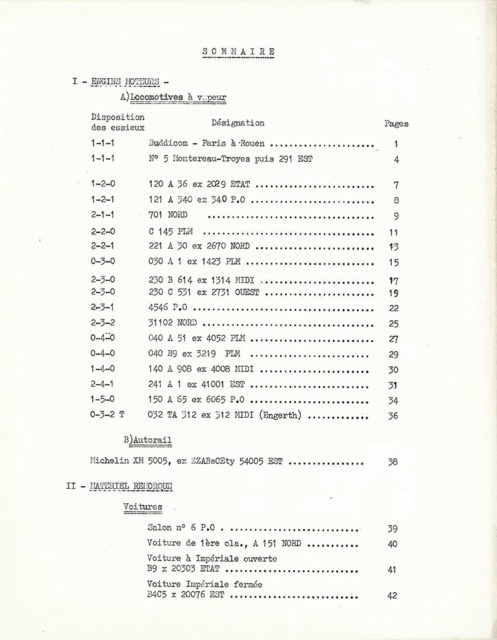

In 1961, Michel Doerr (1919-1995) provided a “list of equipment brought together in the depot in Chalon-sur-Saône with a view to setting up a railways museum”. 70 years after it was established, this document describing the equipment preserved as heritage by the Equipment Department of SNCF has in turn become a heritage asset. It laid the foundations of the future museum and also told of the commitment of a man who was a railways specialist and a singular artist, who, according to the author and journalist Jean des Cars, succeeded in building up “one of the finest collections in the world”. In 1964, the man who is affectionately called “l’ami Doerr” contacted André Malraux, then Minister for Culture, in order to put the collection on display. His way of presenting his approach as “unusual” was not insignificant. The Ministry for Culture had been set up five years earlier in 1959, and the minister chose to direct his efforts towards artistic museums. The Ministry for Transport thus became the leading State partner.

The railways of yesteryars… For a French railways museum

Museums have not been devoted to painting because painting was dead, no more than those devoted to porcelain or to any other manifestation of the human spirit; their essential role is to show the generations of visitors what they owe to those who went before them. That will also be true of the Railways Museum, which will demonstrate through tangible facts the relationship between the continuity of principles and achievements in the development of a railway system that is ever more efficient, and the almost regular changes that result from advancing techniques which are perpetually renewed”.

Daniel Caire

editor in chief of AFAC, 1965

11965 marked a turning point in the plan to set up a French museum devoted to the railways. That was the year when AFAC published a catalogue made up of “historical entries on equipment brought together with a view to setting up a Railways Museum”. The document, drafted by Michel Doerr, presented the 37 locomotives, carriages and wagons that were preserved at the time in Chalon sur Saône. Right from the foreword, Daniel Caire, editor in chief of AFAC, put down the markers of unwavering thought: the railways heritage is human, artistic and technical, and is ever changing. Given that, how is a collection in movement to be conserved, displayed and showcased?

Five years on, in 1970, in an article in the magazine Equipement,-Logement-Transport titled “Towards a French Railways Museum”, Michel Doerr and André Portefaix, Chief Engineer at SNCF, suggested several solutions. For the two men, “[…] we need to think of a museum, especially since museum science has made progress that makes it possible to effectively bring together the appeal of a show and the value of information”.

An exceptional reader:

Jean-Mathis HORRENBERGER (1929-2012)

The book Le Musée Français du Chemin de Fer : une utopie devenue réalité published in 1997 is a valuable account of the life of its author, Jean-Mathis Horrenberger. He describes his childhood in Thann, marked by travelling on board the simple railway carriages of Alsace. Above all, he recounts his first aesthetic shock one evening in 1936 in Marseille Saint-Charles station, when a Mountain 241 locomotive pulled in. He was seven, and paid leave had been instituted.

That was the unforgettable moment when Horrenberger caught what he himself calls a “virus”: that of railways. After World War II, the youngster, later a senior manager of a textile factory in Alsace, avidly read La Vie du Rail and dreamt of joining AFAC, whose editor in chief, Daniel Caire, became his tutelary figure. The publication of the catalogue in 1965 was the trigger for what would eventually be the epic of the creation of the museum.

The obviousness

of Mulhouse

Nine months after his reading the AFAC catalogue, Jean-Mathis Horrenberger officially contacted its President Georges Manas. Nine months of gestation for drafting a complete and resolutely Alsatian project. With its rich industrial and railway past and its position at the crossroads of Europe, the cité du Bollwerk was the ideal location for a museum devoted to railways. The provisional committee responsible for defending the choice of Mulhouse promoted by SIM, already made up of local personalities and members of SNCF, thus offered an additional argument: the “mill house” would also be the home of trains.

From Saône

to Doller

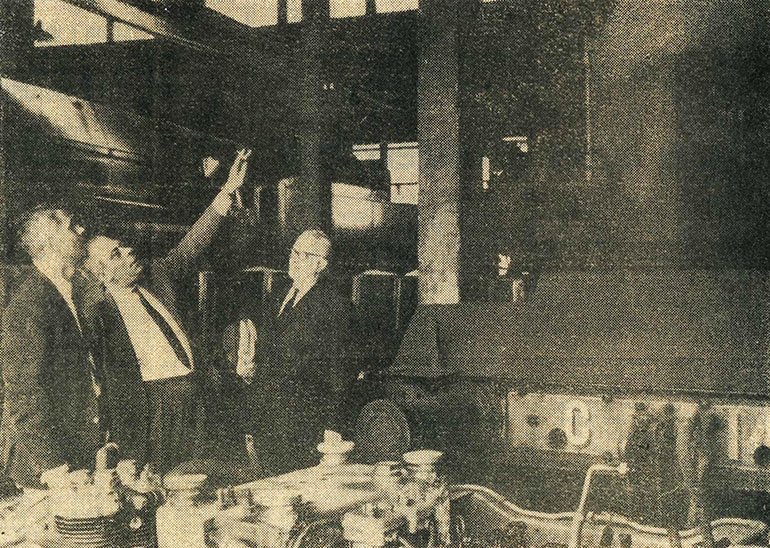

End of May 1966. 300 kilometres away from Mulhouse, the project picked up speed. In the roundhouse in Chalon-sur-Saône, a historic meeting took place between three men: Michel Doerr, Daniel Caire and Jean-Mathis Horrenberger. Charles Baschung, journalist from L’Alsace, sent specially for the event, gave an account in the newspaper of the almost cinematic nature of the meeting. The suspense was unbearable. Would Mulhouse be chosen? Time was short and other cities like Bordeaux, Compiègne and Reims or even Saint-Savin-Sur-Gartempe were also in the running. In his memoirs, Jean-Mathis Horrenberger tells of his astonishment at the extremely damaged condition of some of the material. The dream would not come true without a major financial cost. In that context, political support from the highest level in government seemed more necessary than ever.

Political

support

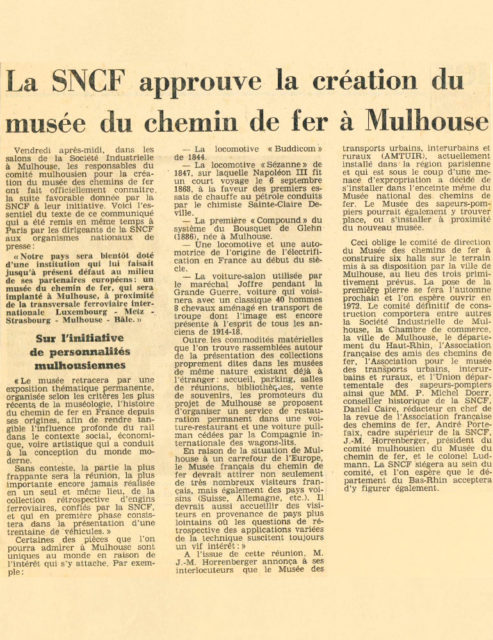

On 28 July 1969, the news was good: SNCF had approved the choice of Mulhouse. A few words in the newspaper Dernières Nouvelles d’Alsace symbolised the success of years of negotiation. This selection of unpublished correspondence from the archives of the Cité du Train bears testimony to that event.