The emergence of a

railway-worker identity

A railway network is not limited to routes, trains and passengers. It is a tentacular system that includes station architecture, workshops, depots, switches, and developments in signalling and rolling stock. People cannot be separated from engineering, and they are symbolised by the great diversity of trades involved and the profiles of passengers. Against that backdrop, each company developed an organisation, values and an aesthetic that were specific to it. The uniforms of railway employees were a particular sign of that sense of belonging.

Between wariness and fascination

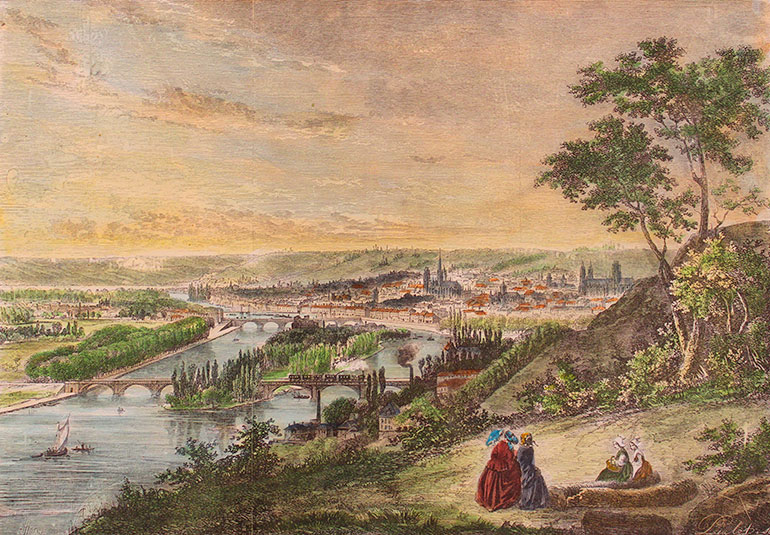

Saying that the coming of the railways was unanimously applauded by the thinkers of the 19th century would be inaccurate. Enchantment and optimism were also accompanied by fear, incredulity, sarcasm and even staunch refusal. The vaudeville show of Salvat and Henri named Le Chemin de fer de Saint-Germain that was put on in the Théâtre de la Porte Sainte-Antoine represents the caustic approach to this new invention, described in the play as a another “fad”. In his Mémoires d’un touriste, Stendhal, residing at Châlon-sur-Saône on 14 May 1838, also regretted the excessive importance given to the productions of “modern civilisation” such as “Diorama and railways”.

It is ironic that a century later, the same city of Chalon would host the first trains that were conserved as heritage objects with a view to creating a French Railways Museum. From the very beginning of the railways adventure, the historical and political character of this mode of transport came to the fore in the press and literature. Defending railways amounted to defending a regime. That was so of the writer and critic Jules Janin, who was close to King Louis-Philippe, and went so far as to say in his Itinéraire du chemin de fer de Paris à Dieppe (1847) that “poetry in the 19th century is that of the steam engine”.

“… If you find the subject (of railways) boring, you are just like me. Nowhere can one escape people saying: “Oh! I am off to Rouen! I have come from Rouen! Are you going to Rouen? The capital of Neustria had never been such a subject of conversation in Lutetia! …”

– 9 June 1843, letter from Gustave Flaubert to his sister Caroline Flaubert

The railway

as a character

In literature, railways are both carriers and characters. The century was marked by the birth of the concept of historical monuments, and that of picturesque stories. By reducing time and distance, the railways contributed significantly to their development. Stendhal, George Sand, Gustave Flaubert and Victor Hugo travelled by rail and told of their experience. In a famous letter sent on 22 August 1837 to Juliette Drouet, the author of Notre-Dame-de-Paris had this to say about his discovery of the Belgian railways. Comparing the engine to a “true beast” Hugo gave it the characteristics of a horse: “it sweats, trembles, whistles, neighs, slows down, rushes away”. A study of contemporary writings shows that personification is very common. A train is a creature full of sound and smell, which excites the senses. In that area, one cannot avoid mentioning La Bête humaine by Zola and Around the world in 80 days by Jules Verne. At the same time, words were joined by pictures. Monet, Courbet, Caillebotte, Van Gogh, Louis Lumière and so many others portrayed the railways in paintings and on film, making them a very artistic subject.

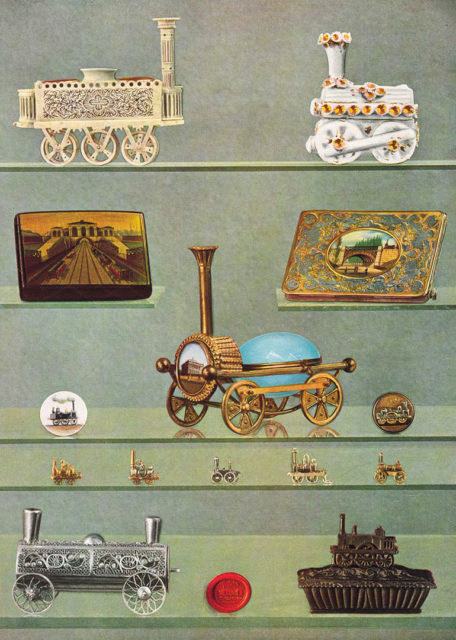

Exhibiting industry

While the public can discover the railways through the tales told by their contemporaries or their own experience of mobility, exhibitions of the products of French industry also showcased the development of railways. These major events were organised in Paris as early as in 1798, to highlight French know-how in a wide variety of areas including textile, cabinet making and metallurgy. A review of the judges’ reports provides valuable information about the representation of the railway industry.

In 1823 and 1827, steam engines were mainly used in farm machinery. In 1839, a great change occurred, when the Railways section first appeared. In the mind of the writer, in spite of the inauguration of the first railway lines, there was no doubt that rail transport was still in its infancy. The author also stressed that France was lagging behind her neighbour across the channel. In 1844, the section was supplemented by a new category, that of “Locomotive machines and railways, tracks and cars”.

One of the gold medallists was Meyer et Cie from Mulhouse, developers of a locomotive named L’Espérance, which was delivered for the Strasbourg Basel line in 1842, soon followed by the Mulhouse, which had been set aside in 1843 for the Paris to Versailles line. The silver medal went to the workshop in Rouen of the Englishmen Allcard and Buddicom, who had created the oldest European locomotive that can be still be found in the Cité du Train, the 1844 Buddicom.

Five years later, in 1849, the judges’ report became even more precise, and now spoke of “Construction of locomotive machines, brake vans, parts and miscellaneous equipment”.

While Derosne et Cail displayed a Crampton system locomotive, other companies presented track components, workshop drawings, car buffers or machines that printed numbered tickets. The public could thus discover the diversity of railway heritage.

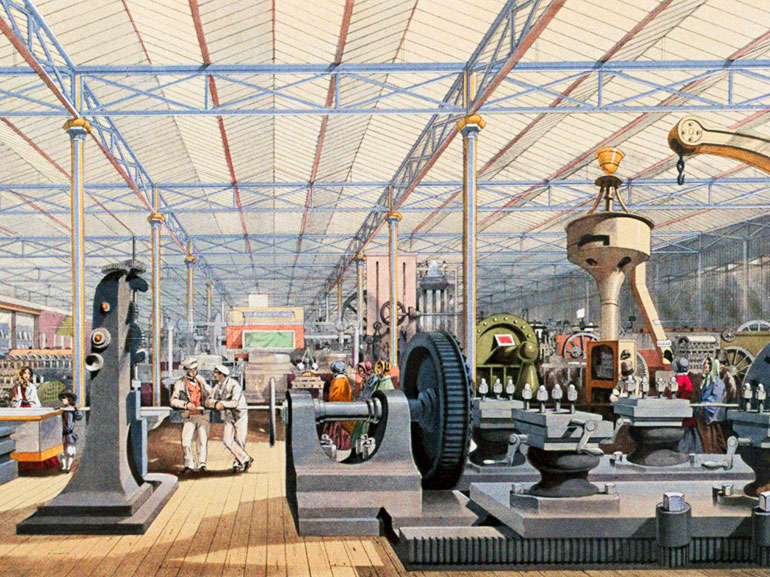

The Crystal

Palace

In 1851, the phenomenon of industry exhibitions went global. Under the glazed roof of the Crystal Palace in London designed by Joseph Paxton, the British advance in engineering and commerce was put on display. The building was originally erected in Hyde Park and was a temple to the Industrial Revolution, hosting a large number of countries that brought their latest artistic and manufacturing creations with them. For one of the main British reporters, John Tallis, the display from France was second only to the United Kingdom in terms of its quality. According to the author of the report, exhibitions of industry products organised in the past in Paris were bearing fruit: the objects presented by the 1750 exhibitors showed a keen sense for detail, not unlike what we would now call “scenography”. Thus, the plan of the palace tells us that on the ground floor, near the aisle devoted to locomotives, a large stall showcased “moving machines”. Indeed, the understanding and promotion of printing and spinning machines required the use of animation.

Behind the scenes in 1855

“Machines cannot be put into motion without being directly supplied by fuel; machines create inconvenience because of their noise and smoke, or because they take up space. That it why steam locomotive engines, nailing machines, distilling equipment, beaters and so on may only be displayed in the galleries in their idle state”.

– Report on the Universal Exposition of 1855, Napoléon-Joseph-Charles-Paul Bonaparte

The London event had left a lasting effect on visitors. As a result, Paris had to do its best. Four years after the Crystal Palace success, France inaugurated its first universal exposition. The report drafted by Napoléon-Joseph-Charles-Paul Bonaparte, the Emperor’s cousin, was of importance against that background, as a remarkable testimonial of the Titanesque preparatory work required by such an event. Indeed, bringing together so many exhibitors is not easy, especially when their intention is to display large objects like railway rolling stock. The writer stressed that the organisation of the Gallery of Machines therefore led to a certain number of compromises. In particular, he pointed out that locomotives, which generated noise and smoke, could only be shown halted.

Trains as

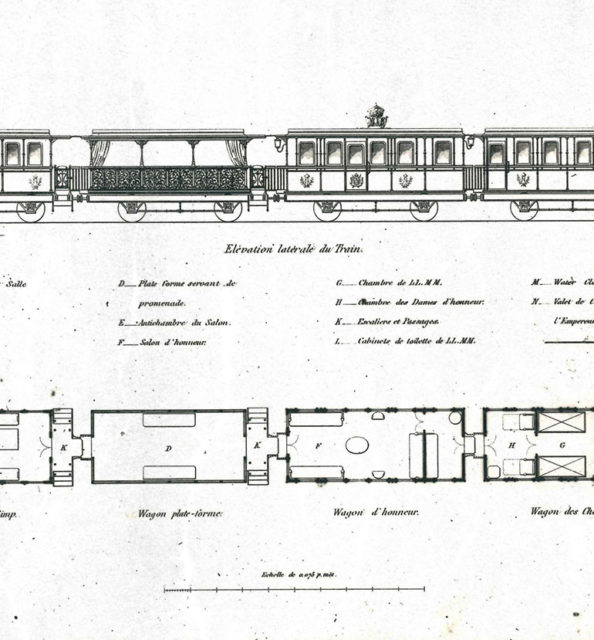

ceremonial spaces

Two years later, while London was inaugurating its Science Museum, the imperial train showed a significantly more delicate aspect of railways. Built by the Compagnie du chemin de fer d’Orléans for Napoleon III and his wife Eugénie, the train was made up of six carriages. These spaces, built under the supervision of the engineer Camille Polonceau based on drawings by Eugène Viollet-Le-Duc, were truly palatial and included a dining room, pantry, salon for aides-de-camps, antechamber, ceremonial room, bedroom, lavatory and wardrobe. A book published in 1857 by the publisher Bance tells us that the composition required five months of work. Salon 6 for Aides-de-Camps can be seen in the Cité du Train, a remnant of that artistic prowess. The car was restored in the 1970s by the Romilly workshop and is decorated in garnet and ultramarine blue. The imperial eagle and the bronze columns give it its refined appearance. Inside, the Emperor’s monogram is encased in a sophisticated floral decor. The types of wood and expensive fabric used create an atmosphere that is warm, yet formal. Salon 6 is a symbol of the eclectic tastes that were in fashion at the time, and is a masterpiece in movement.